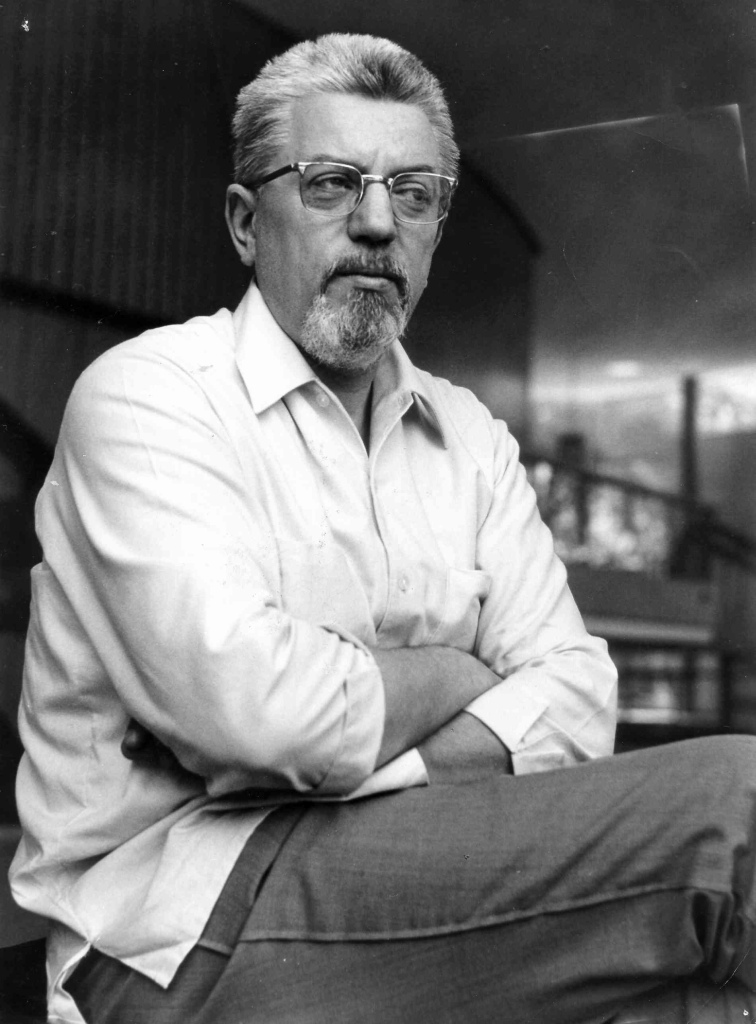

One of the most important German composers to emerge during the post-World War II era, Bernd Alois Zimmermann was born in the outskirts of Cologne in 1918. His schooling at the Cologne Musikhochschule was interrupted when he was drafted for military service in the early days of the Second World War. Discharged in 1942, Zimmermann resumed his academic training with Jarnach and Lemacher, and between 1948 and 1950 enrolled in the summer courses at Darmstadt. He was engaged as a lecturer in music theory at Cologne University in the early years of the 1950s, and, from 1957 on, taught composition at the Cologne Musikhochschule.

musicus, organicus

presents

Bernd Alois Zimmermann — The Life You Give

In celebration of his life in music

March 20 at 1 pm EST

on Clubhouse

Until his untimely death in 1970 Zimmermann produced a steady stream of music for both concert and radio (having been director of not only composition at the Musikhochschule but also radio, film, and stage music as well). In 1965 his “pluralistic” opera (so called because it incorporates elements of many different musical styles, juxtaposing live orchestra with electronic sounds and utilizing a fair amount quotation as well) Die Soldaten was successfully premiered in Cologne. The work, perhaps Zimmermann’s most eloquent musical statement, has since been hailed as the greatest operatic achievement since Alban Berg’s Lulu.

Zimmermann’s music frequently borders on unplayability, and it is only through the exceptional gifts of a handful of players and conductors (including cellist Siegfried Palm and conductor Hans Rosbaud) that his powerful musical creations escaped oblivion. His work reveals a deeply religious sentiment (as in the second volume, sub-titled “devotional exercises” of the solo piano work Enchiridion, or the viola concerto Antiphonen from 1962), and in later years Zimmermann, increasingly withdrawn from the musical establishment (indeed, from the rest of the world as well), came to view his music as a personal act of communication with the Divine. His final work, an “ecclesiastical action” for two speakers, bass, and orchestra, completed just five days before his death, concludes with a quotation of J.S. Bach’s chorale Es ist genug.

by Blair Johnston / Source: all music

Die Soldaten / The Soldiers

Opera in four acts

Libretto: Bernd Alois Zimmermann after Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz

Premiere: 15 February 1965, Cologne (Opernhaus)

Cast

WESENER (bass)

MARIE (very dramatic coloratura soprano)

CHARLOTTE (mezzo-soprano)

WESENER's OLD MOTHER (low contralto)

STOLZIUS (youthful high baritone)

STOLZIU's MOTHER (very dramatic contralto)

OBRIST (bass)

DESPORTES (very high tenor)

PIRZEL (high tenor)

EISENHARDT (heroic baritone)

HAUDY (heroic baritone)

MARY (baritone)

COUNTESS DE LA ROCHE (mezzo-soprano)

HER SON (very high lyrical tenor)

CHORUS

officers, soldiers, servants, people

Place

Time

yesterday, to-day and to-morrow

ACT I In the home of Wesener, a merchant who has moved to Lille with his daughters from Armentières. Charlotte, the elder sibling, is embroidering as her sister Marie writes a letter to the mother of Stolzius, her fiancé back in Armentières. Desportes, a young military officer and nobleman, visits Wesener’s shop, intent on seducing Marie. Desportes asks her father for permission to take her to the theatre, but he refuses. Alone with his daughter, Wesener explains that soldiers are famous for ruining poor girls’ reputation. Outside the barracks, the soldiers discuss the influence of the theatre on their behaviour. Haudy argues that theatre is more fun than any sermon, while Eisenhardt believes that soldiers should be subject to the same moral restrictions as civilians. At home, Wesener insinuates to Marie that a relationship with the captain could be socially beneficial to the family, and suggests that she should not tell Stolzius anything yet. Left alone, Marie can’t help but feel guilty. ACT II In Madame Roux’s café, soldiers drink and play cards. Pirzel argues with Eisenhardt, who takes a dim view of the soldiers’ mockery of Stolzius based on rumours about his fiancé Marie. When Haudy enters the café with Stolzius, the soldiers make ironic remarks. Marie tells Desportes that Stolzius is angry with her, and Desportes offers to write a letter in reply. Marie decides to break up with Stolzius and surrender to Desportes. The situations overlap. On the one hand, Stolzius’ mother chastises him for being in love with a «soldier’s whore», while on the other, Wesener’s elderly mother sings a folksong about lost innocence. Stolzius swears to take revenge against Desportes. ACT III Eisenhardt and Pirzel chat about the arrival of Desportes’ friend, Captain Mary. Stolzius visits Mary after deciding to join the army under Mary for the sole purpose of murdering Desportes. At the Wesener home, Charlotte chastises Marie for accepting Mary’s gallantry. She replies that Desportes has abandoned her and that this is the only way to keep in touch with him. As Charlotte argues with her sister, she is interrupted by Mary, who has come to invite her to take a walk. They all leave, accompanied by Stolzius, unrecognised by Marie. Countess De la Roche waits impatiently for her son to come home. He started a relationship with Marie shortly after she was dumped by Mary. The Countess gives him a severe dressing down, and advises him not to go on seeing a lower class girl. At Wesener’s house, the sisters argue over Marie’s attempts to make Mary jealous by accepting the young count’s gifts. They are visited by the Countess, who cruelly confronts Marie with the truth: a relationship with her son is impossible. ACT IV Marie’s past, present and future overlap in her nightmares. Stolzius decides to poison Desportes. As he serves the table where Mary and Desportes are sitting, the officers jeer about Marie. Tired of her whims and convinced that «she is no better than a whore», they left her in the hands of Desportes gamekeeper, who raped her. Stolzius reveals his identity when the poisoned soup takes effect, and then commits suicide. Endless lines of soldiers and fugitives cross paths in the city limits. Wesener meets his daughter on the street. She is now a beggar, and he does not recognize her.