Kitano Takeshi, born January 18, 1947, in Tokyo, Japan, is the actor, director, writer, and television personality known for his dexterity with both comedic and dramatic material.

Kitano was born into a working-class family in Tokyo. He planned to become an engineer but dropped out of college to enter show business in 1972. With his friend Kaneko Kyoshi, he formed a popular comedy team called the Two Beats, and Kitano would frequently act under the name Beat Takeshi. Performing first in nightclubs, the duo soon began to appear on Japanese television and quickly attracted a national following with their irreverent, sometimes off-colour routines. In the late 1970s Kitano embarked on a solo acting career. He starred in a television series called Super Superman and in several movies. In 1983 he appeared alongside David Bowie and Tom Conti in his first English-language film, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence.

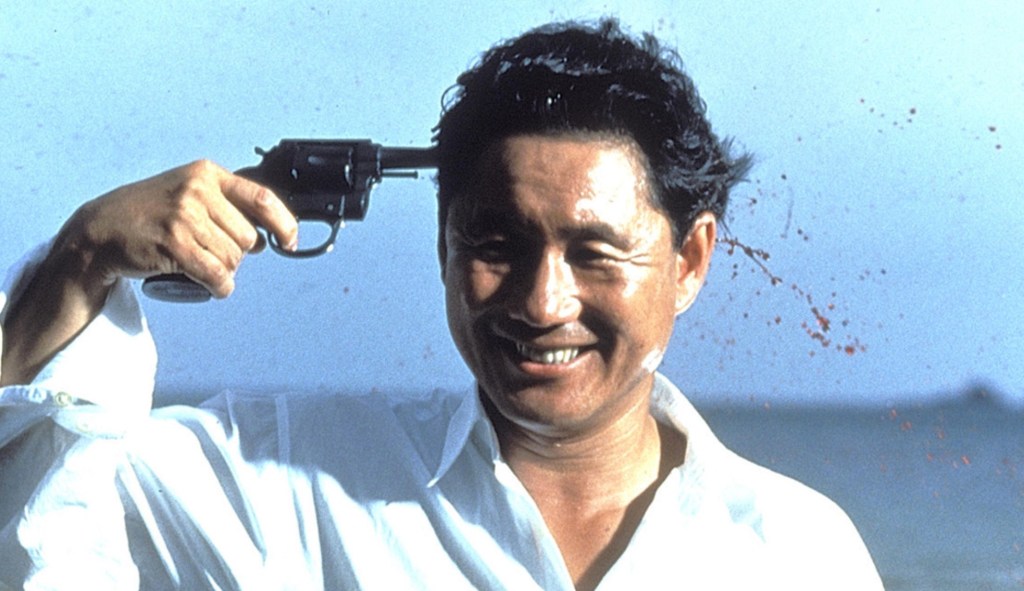

In 1986 Kitano was arrested for breaking into the offices of a tabloid and assaulting staff members in a dispute over the veracity of claims that had been published about his personal life. That year he also began hosting the game show Takeshi’s Castle (1986–89), in which contestants were required to compete in a series of comical physical challenges. The show was broadcast internationally in a variety of condensed versions, usually with commentary mocking the contestants. Kitano made his directorial debut in 1989 with Sono otoko, kyōbō ni tsuki (Violent Cop), in which he also played the title role. The film, about a Tokyo detective trying to crack a yakuza (“gangster”)-run drug ring, drew comparisons to Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry (1971) and was the first in a series of crime epics that included 3–4x Jūgatsu (1990; Boiling Point) and Sonatine (1993). He also penned the screenplays for the films—though his work on Violent Cop was uncredited—and he wrote many of his subsequent movies.

In 1994 Kitano was in a serious motorcycle accident that necessitated months of physical therapy. He rebounded with Hana-bi (1997; Fireworks), another tale of policemen and yakuza; the film was lauded for its deft blend of comic and tragic elements and for its innovative use of flashbacks. In addition to winning a Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, it was also selected as the best non-European film by the European Film Academy in 1997.

In 2000 Kitano directed Brother, his first film with an English-speaking cast. That year Kitano also appeared in Batoru rowaiaru (Battle Royale), a futuristic thriller that stirred controversy in Japan with its tale of juvenile delinquents forced by authorities into deadly combat on a remote island. He later starred in its sequel, Batoru rowaiaru II: Chinkonka (2003; Battle Royale II: Requiem). Kitano abandoned his preoccupations with comedy and violence in Dolls (2002), which tells three separate love stories. In Zatōichi (2003; Zatōichi: The Blind Swordsman), he broke new ground with his first period piece, in which he played a legendary blind samurai.

In Takeshis’ (2005), which he also directed, Kitano parodied his public image as a star with a bloated ego, playing a version of himself as well as his own doppelgänger. He followed with two further films featuring incarnations of himself: Kantoku Banzai! (2007; Glory to the Filmmaker!) and Akiresu to kame (2008; Achilles and the Tortoise). Kitano contributed One Fine Day to Chacun son cinéma (2007; “To Each His Own Cinema”), a collection of short films in which the director of each segment attempted to articulate his feelings about cinema. He returned to the yakuza genre in 2010 with the ultraviolent Autoreiji (Outrage). The sequels Autoreiji Biyondo (Beyond Outrage) and Autoreiji Saishusho (Outrage Coda) appeared in 2012 and 2017, respectively.

In addition to hosting a range of television shows and immersing himself in the filmmaking process, Kitano was also a newspaper columnist and a stand-up comedian. He published several novels and a collection of short stories, Shounen (1992; Boy). Kitano wrote memoirs about several periods in his life, including Asakusa kiddo (1992; “Asakusa Kid”; filmed 2002), about his childhood in Tokyo.

By Sherman Hollar / Source: Britannica

“Dolls”

Dolls [2002] – Moving Tales of Undying Love Illustrated by Stunning Poetic Imagery

“I wanted to make movies that can’t be pigeonholed. I want audiences to come out of this film not knowing what to say or what to think”, says the multi-faceted Japanese artist Takeshi Kitano (aka ‘Beat’ Takeshi). Mr. Kitano is one of Japan’s top media personalities. He is a poet, recording artist, actor, and once a stand-up comedian. But the most revered of his identities is when he masters the triple roles of ‘writing-direction-editing’. Although it’s hard to say what subject Mr. Kitano would plunge himself into in his subsequent films, there are few recurring elements in his film (good enough to be called as ‘Kitano-esque’). His best films are known – Sonatine, Hana-bi, Zatoichi – for their brilliant juxtaposition of harsh violence and poetic realism. Thematically, Kitano’s works keeps on brooding over love, existence, and fate. Furthermore, Kitano’s protagonists are mostly tough-guys (sometime Yakuza figures) whose deep sensitivity escapes through their hardened facial features over the narrative course. The editing and directorial style of sweetly swerving Kikijuro might be totally different than violent genre pictures like Brother, Outrage or Zatoichi. In spite of the wildly changing formal schemes, a bewitching, lamentable tone could be unmistakably felt in Takeshi Kitano’s cinema.

After facing lukewarm response to his American debut Brother (2000), Kitano distanced himself from restrained gangster films to attempt his most free-flowing movie yet. Kitano’s languidly paced art-house feature Dolls (2002) prioritizes visual lyricism over predefined narrative arc. Dolls portray three loosely interconnected tales, circling around the themes of love, obsession, and loss. The three stories of doomed love are full of achingly beautiful images, although its intended meaning (if there is one) isn’t always easy to grasp. The film opens on a literal stage with a Bunraku performance (traditional Japanese puppetry). The visible doll handlers control the sad characters (of this tale) as per the narrator’s voice. Subsequently, the puppets become the spectator and witness dramatic tales of tragic love. A young white-collar worker Matusmoto (Hidetoshi Nishijima) breaks off engagement with his true love Sawako (Miho Kanno) to marry the boss’ daughter. A decision heralded by his colleagues and forced upon by Matsumoto’s parents. Sawako in a state of despair attempts suicide and ends up in near-catatonic state. Burdened by guilt, Matsumoto runs away on his wedding day and kidnaps Sawako from the hospital.

He decides to drop out of the society with her and go through a journey of reconciliation. The non-talkative, child-like Sawako is bound by a long red silk cord that binds her to Matusmoto. When we first see the lovers, the red cord brushes through the cherry blossoms, while people gathered around tease them as ‘bound beggars’. An aging Yakuza boss Hiro (Tatsuya Mihashi) with an existential crisis one day visits a park, where he discovers the girlfriend Ryoko (Chieko Matsubura) he once had abandoned as a young man, still anticipating his (every Saturday) return at the park bench. A famous pop-star Haruna Yamaguchi (Kyoko Fukada) inspires idolatry among the alienated men. Nukui (Tsutomu Takeshige), an introverted traffic controller, is one of her most devoted fan. When the pop idol is caught in a car accident which slightly disfigures her face, Nukui takes extreme measures to prove his ardent love. The pair of bounded star-crossed lovers passes through different seasons and also the principal players of other tales, while teetering towards their inevitable fate.

Kitano’s movies are familiar for slight surrealistic or magical realist touches amidst the formal mode of restrained naturalism. In Dolls, the narrative is entirely diffused with hyper-reality and magical realism. The stylistic opening passage of the Japanese Bunraku performance sets the stage for film’s unreal aesthetic appearance. Since it’s the dolls that use humans as form of puppet characters, Kitano’s atmospherics are tinged with sumptuous imagery which isn’t necessarily realistic. The deliberate theatricality of the aesthetics is designed to circumvent the conventional dramatic tension. The bound beggars’ journey through four seasons is captured in glorious color schemes. Matsumoto and Sawako’s costumes progress down from modern-day dress to traditional Japanese robes (majestically designed by famous costume designer Yohji Yamamoto) as they shuffle through sunny land patches, cherry blossoms of spring, red maple leaves of autumn, and white snow of winter (glorious cinematography by Katsumi Yanagishima). The sharply contrasting flow of seasons may indicate the lovers’ impossibility from liberating themselves from the cycle of misery and fate. The extravagant costumes and the color-coordinated landscapes keep intact with fanciful imagery, since in real life the homeless lovers’ would be dirty, and dressed in tatters. At one point, we see the red-color maple leaves moving on to snow, as the camera pans up to showcase vast snow-capped landscape. Director Kitano says he included the shot to denote “it’s as if it was a play, and the set is being changed.”

The three tales aren’t attached with huge emotional appeal. Their lives are destroyed by some strange twist of fate. Moreover, the characters themselves make mistakes and spoil the love rather than exterior forces. The mistakes are done out of self-love and free-will. And, the amends are made through stranger ways too. The lovers’ gestures to uphold the spirit of love may seem ultimately pointless, but it definitely provokes our empathy. The stretched-out acts of repentance also lead to devastating, yet beautiful images. The theme of looking is consistently established from the beginning of the narrative. Shots are often visualized in subjective mode with the blank-faced characters often watch over something: an angel toy, stomped butterfly, maple leaves, etc. This subjective mode underlines the film’s magical realist vision. The Bunraku references and other deep layers of symbolism might be lost over those not well-versed in Japanese culture (like me). Dialogues, as usual are kept to bare minimum. Nevertheless, the emotional purity of the characters easily penetrates through the narrative’s placid surface. The haunted, repressed expressions of anguish from Nishijima and Miho Kanno (the central pair of lovers) are thoroughly heartbreaking. Miho Kanno especially wrings our tear in more than one occasion. The scene of her bursting into tears over the inability to play with broken toy effortlessly heightens our emotional pains. Most agonizing was the scene towards the end, when Matsumoto hugs Sawako, begging her forgiveness, after she clutches her silver chain, in a brief moment of epiphany.

Those who have the patience to emotionally invest themselves in Dolls (113 minutes) would be rewarded with a dazzling and deeply affecting movie experience. Takeshi Kitano, despite taking occasional self-indulgent turns, depicts these very simple tales of love & loss in a mesmerizingly powerful manner.

Source: Passion for Movies

Dolls takes puppeteering as its overriding motif — specifically, the kind practiced in Bunraku doll theater performances — opening each section of his film with a story provided by the puppets and their masters, which relates thematically to the action provided by the live characters. Chief among those tales is the story of Matsumoto (Hidetoshi Nishijima) and Sawako (Miho Kanno), a young couple whose relationship is about to be broken apart by the former’s parents, who have insisted their son take part in an arranged marriage to his boss’ daughter. He initially agrees, causing the unstable Sawako to be committed to a psychiatric hospital. When he leaves his new bride at the altar to save Sawako, however, he realizes that she’s so incapable of caring for herself that she needs to be tied to him with a red rope. Inextricably bound, the two wander through Japan, encountering others along the way who have similarly overlooked love for other, more fleeting pleasures: fame, power, money.

Source: all movie

“Zatōichi – The Blind Swordsman”

Takeshi Kitano, better known under his acting pseudonym “Beat” Takeshi, is a man of many, many talents. He’s a skilled writer, author, screenwriter, painter, director, presenter, poet but more than anything else, in Japan he was known as a comedian – as part of the comic double act The Two Beats, and for hosting shows such as Takeshi’s Castle. So it was a bit of a surprise when, in 1983, he starred in war drama Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence. His film career began to explode when he starred and directed Violent Cop, the story of which seems pretty self-evident, and a number of other slow, dramatic and violent films such as Sonatine, Boiling Point, Hana-Bi, and so on. Western Audiences, myself included, probably got their first taste of Kitano when he played the ruthless teacher in Battle Royale, and assumed he was never a really goofy, light-hearted kind of person.

These two drastically different views on Kitano come neatly together in his 2003 film Zatoichi. A reboot of sorts of the wildly popular chanbara-genre Zatoichi films of the 60s and 70s, about a blind masseur who is also a master swordsman, this was the last film he directed before his trilogy of surreal pseudo-autobiographies, and was Kitano winking at the audience, telling us that beneath all the darkness and violence was the same genre-savvy renaissance man we know and love.

In the film, Ichi (or Zatoichi, played by Beat Takeshi), finds himself in a village oppressed by a gang lord, like villages in chanbara films are prone to be. He decides to stay and protect the villagers from the gang war that is brewing, and befriends farmer Ume (Michiyo Okusu), and her dopey gambler nephew Shinkichi (Guadalcanal Taka). Meanwhile, a ronin (Tadanobu Asano) accepts a position as bodyguard for the yakuza, in order to support his sick wife (Yui Natsukawa), and two Geisha (Daigoro Tachibana and Yuko Daike) return to the village to exact revenge on the gangsters who killed their family.

There’s a lot of plot here to go around, and Kitano tells all three stories well, intertwining them with each other to make it work as one big plot. Usually a film with so many threads can unravel quite quickly, but here it’s told as if every story affects the others, which they do. The ronin Hattori’s tale is probably the most detached from the rest of them, and so happens to be the one with the least time dedicated to it. It’s small, but effective in showing that the people who work for Ginzo (Ittoku Kishibe) aren’t necessarily horrible people. Hattori is a man without a choice, who does what he does because he’s good at it. The geisha’s story is more mixed in with Zatoichi’s, and because they spend a lot of time with him, they blend in better and feel more connected to the larger story. All three would be very entertaining by themselves, but together, they work towards a bigger picture, about what it takes to live in this time.

If this sounds a bit too dark and hard-hitting, worry not. Winking to Kitano’s manzai past, Zatoichi is sprinkled with small comedic moments all over the place, from the rice farmers dancing to the soundtrack, making almost Stomp-like sounds to the rhythm, to the affable idiot who lives next door and wants to be samurai, but just runs around the house screaming at the top of his lungs. Kitano knows that the world isn’t all doom and gloom, and that there are funny moments even when your village is under siege, and is he willing to bend the rules a bit to make his film stand out a bit more. The film ends with a fantastic 8-minute long tap dancing sequence. The blood is stylized CG (and the swords are sometimes too, and boy have they not aged well). Zatoichi walks around with peroxide white hair, and a bright red cane – as a means of separating this incarnation with the previous series both visually and stylistically. While keeping true to the spirit of the genre, he spins it his own modern way, which is a risky move. Not everyone can pull it off but Takeshi Kitano makes it one of the strongest and most recognizable aspects of the film. The lightness takes the edge off a film that would otherwise be two hours of misery, violence, revenge and people trying to kill a blind guy.

Part of what makes Zatoichi so entertaining is the cast, who all pull their weight and allow the film to have this rich palette of emotion and tone, though it’s true that this only applies to the main cast. Ginzo, the primary villain, doesn’t have a lot going for him outside of the simple role of yakuza boss and his existence is only there for the geisha to grow their characters from. Likewise with Hattori’s wife Shino. When she isn’t telling him not to go back to his old life, she isn’t on screen. Her purpose begins and ends with the ronin. But in a way, that’s fine. The main cast consists of six already – more would clutter the film too much and drag it on for hours.

It stands as its own film, without any prior knowledge of the series, and serves as a great introduction to the character of Zatoichi. Chances are you’ll get a lot of enjoyment out of this, even if you’re not too into samurai films.

Source: Asian Cinema Critic

Leave a comment