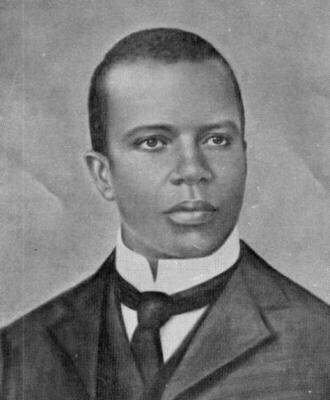

Scott Joplin, born November 24 1867 or 1868, in Texas, USA, is the composer and pianist known as the “king of ragtime” at the turn of the 20th century.

Joplin spent his childhood in northeastern Texas. By 1880 his family had moved to Texarkana, where he studied piano with local teachers. Joplin traveled through the Midwest from the mid-1880s, performing at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Settling in Sedalia, Missouri, in 1895, he studied music at the George R. Smith College for Negroes and hoped for a career as a concert pianist and classical composer. His first published songs brought him fame, and in 1900 he moved to St. Louis to work more closely with the music publisher John Stark.

Joplin published his first extended work, a ballet suite using the rhythmic devices of ragtime, with his own choreographical directions, in 1902. His first opera, A Guest of Honor (1903), is no longer extant and may have been lost by the copyright office. Moving to New York City in 1907, Joplin wrote an instruction book, The School of Ragtime, outlining his complex bass patterns, sporadic syncopation, stop-time breaks, and harmonic ideas, which were widely imitated. Joplin’s contract with Stark ended in 1909, and, though he made piano rolls in his final years, most of Joplin’s efforts involved Treemonisha, which synthesized his musical ideas into a conventional, three-act opera. He also wrote the libretto, about a mythical black leader, and choreographed it. Treemonisha had only one semipublic performance during Joplin’s lifetime; he became obsessed with its success, suffered a nervous breakdown and collapse in 1911, and was institutionalized in 1916.

Joplin’s reputation as a composer rests on his classic rags for piano, including “Maple Leaf Rag” and “The Entertainer,” published from 1899 through 1909, and his opera, Treemonisha, published at his own expense in 1911. Treemonisha was well received when produced by an Atlanta, Georgia, troupe on Broadway in 1972, and interest in Joplin and ragtime was stimulated in the 1970s by the use of his music in the Academy Award-winning score to the film The Sting.

(Source: Britannica)

Scott Joplin composed three works for the stage. The first, The Ragtime Dance, depicted a typical African-American dance gathering; it was performed in 1899 at the Black 400 Club in Sedalia, Missouri. The second work, A Guest of Honor, about Booker T. Washington’s dinner with Teddy Roosevelt at the White House, premiered in East St. Louis, Illinois, in 1903. Joplin took the production on tour. A series of financial mishaps, however, ended the performances. The score is now thought to be lost.

Joplin’s third stage work was the opera Treemonisha. The libretto, also written by the composer, tells the tale of the adopted daughter of former slaves Ned and Monisha. Because the baby was found under a tree, she is named Treemonisha.

Treemonisha

Scott Joplin’s “Treemonisha” first premiered as a concert read-through in Harlem in 1910, and was not fully staged until 1972, over fifty years after the composer’s death The work, described as “an entirely new form of operatic art,” combines Wagnerian conventions of opera with traditional African-American folk tales and music. Joplin, writer of the score and libretto, may have created the opera to parallel his own life and values, particularly the desire to learn and the idea of education as freedom from ignorance.

“Treemonisha” was first revived by the Atlanta Symphony in collaboration with the glee club of Morehouse College. Led by conductor Robert Shaw, the 1972 performance succeeded in introducing Joplin’s operas to a wider audience. Just a few years later, “Treemonisha” premiered at the Houston Grand Opera and became a hit across American stages.

In 1976, Joplin received a posthumous award for the Pulitzer Prize in music. “Treemonisha” has been identified as a lasting piece of American operatic history for its promotion of women and African-Americans, infusion of American folk music and European opera, and emphasis on community, education, and hard work.

Short Plot Summary

Joplin’s opera is the story of Treemonisha, the titular character and a young woman living in a forest between the composer’s hometown of Texarkana, Texas and the Red River of Arkansas. The piece begins with the community beginning their day of work with folk songs. Treemonisha finds herself under a sacred tree in the forest, a direct parallel to the enchanted tree of “Die Walkure.”

Source: opera wire

“Treemonisha” takes place on a plantation in Texarkana, where African Americans made up a quarter of the population as voters, politicians, preachers, sharecroppers, and landowners. The world premiere portrayed Black working class life in a realistic and respectful manner, moving away from traditional stereotypes. The plot: In 1866, Monisha and Ned longed for a child and their wish came true as they found Treemonisha under their “Sacred Tree.” They hid their

family formation narrative from everyone. When Treemonisha was seven, Monisha bartered her

maids-work and Ned’s woodchopping for Treemonisha’s education by a white woman, mirroring Joplin’s life. At a time when “The Moynihan Report” promoted the concept of the degenerative African American mother and family, the world premiere portrayed the Black family as Melvin

Drimmer of “Phylon” wrote as “a strong well-knit Black family, magnanimous in victory and virtuous.” As the opera begins 18 year-old Treemonisha returns home, ready to teach and lead, embodying African American woman power. She finds Conjurer Zodzetrick, embodying the African trickster God Papa Legba, peddling African religious/magical practices— “bags of luck.”

Being brave, Treemonisha confronts him, “You have caused superstition and many sad tears, you should stop, for your doing great injury.” Zodzetrick threatens Treemonisha, but is stopped by Remus, Treemonisha’s love interest. The couple banish the conjurers. Joplin follows the common ideology of uplift of maligning African traditions, as James Weldon Johnson noted revolting “against anything connected with slavery.”

After the expulsion of the conjurers, the community comes together to husk corn. Treemonisha

proposes “A Ring Play” –hambone, songs, and ring games which African slaves brought to the U.S., evoking Joplin’s childhood memories. They sing “Goin Around” which Dr. Anderson contends that Joplin choreographed given he “has dance steps written in the score…[placing him] years ahead of Arnold Schoenberg’s [“Moses and Aron”].”

Later, Treemonisha notices that her friend Lucy wears a head wreath while she wears a ribbon.

Lucy suggest “you should wear a wreath made of pretty leaves.” Treemonisha goes to her “Sacred Tree” to gather leaves, but Monisha protests, recounting their family formation, of how “the rain or the burning sun you see, would have sent you to your grave, But sheltering the leaves that old tree, your precious life did save. So now with me you must agree, Not to harm that sacred tree.”

“The Sacred Tree” represents survival, hope, and the coded spiritual “Run Mary Run’s” refrain: “you’ve got a right to the tree of life.” Treemonisha and her parents pledge their love for one another, and Treemonisha and Lucy set out in search of leaves.

Back at the Plantation, Parson Alltalk sermonizes “Good Advice,” but is interrupted by Lucy disheveled, gagged, and bound. Lucy saved herself from the conjurers, a “symbol of women’s liberation,” using her African American woman super power. Lucy recounts her misadventure and Treemonisha’s captivity. The neighbors cry-sing in what Anderson describes as “a system

of notation for a cross between speaking and singing,

” a Joplin invention created before Schoenberg’s sprechgesang. Remus dressed as an “ugly scarecrow” and the men set off to save Treemonisha.

In the forest, Zodzetrick and Treemonisha arrive as his minions sing about “Superstition.” They decide to throw Treemonisha into “The Wasp-Nest,” but spotting the “De devil” (Remus), they scamper away. Saved, the couple make their escape out of the forest and happen upon an

acapella quartet singing “We Will Rest Awhile” in the cotton field. In this song, Joplin uses the African American invention—the barbershop quartet. Treemonisha and Remus continue their trek and meet workers who invite them to dinner because “Aunt Dinah Has Blowed De Horn.” The 1972 production discarded Minstrelsy and the Hungry Negro stereotypes. It took great care

to present these scenes and the African American working class respectfully.

Meanwhile, at the cabin, Ned choruses Monisha’s bewailing “I want to See My Child Tonight…I

would rescue her or go insane.” Monisha crushes “The Moynihan Report’s” degenerative Black mother, by showing the loving, devoted fierceness of Black motherhood. The couple annihilate “Moynihan’s Report” as a loving family. They will their daughter home. The captured conjurers soon follow. The women want revenge– “punish them!” Treemonisha pleads “give them a severe lecture, and let them freely go, ” to no avail. Remus joins her protestations singing “Wrong Is Never Right, ” again to no avail for the neighbors want vengeance–

“the conjurers should be dispatched to the other sphere, to make old Satan feel glad.” Treemonisha finally prevails. With the spirit of forgiveness embraced by the community, Treemonisha proposes that

“[w]e ought to have a leader in our neighborhood,

” and the community sings “we will Trust you as Our Leader,” and bestow upon Treemonisha the crown of leadership. At this joyous occasion, Treemonisha leads the community, “The Slow Drag,” the finale choreographed by Joplin. She sings– ”salute your partner, do the drag… Marching onward, Marching to that lovely tune.”

Source: Library of Congress

Leave a comment