The 20th century

Important symphonists of the early 20th century include many non-Germans. Carl Nielsen and Jean Sibelius, the former Danish, the latter Finnish, both owe much to the Viennese symphonists but acquired individual styles that resulted in new conceptions of symphonic form. Nielsen’s six symphonies display a kind of unity based on “progressive” or “emergent” harmony, one key moving on to the next in such fashion that the gamut of harmonies in a single symphony (or movement) does not totally relate to a single tonic. His harmonies sometimes fluctuate between two or more goals and incorporate chromatic and modal features. This nontraditional harmonic tension is an aspect of the breakdown of normal Classical ways of establishing tonality, for which the 19th century (and Wagner in particular) is largely responsible. (Nielsen, however, was an anti-Wagnerian.) This “destructive” impulse, elements of which may already be heard in Haydn, led to constant reevaluation of the basis of sonata form and hence of the symphony as a whole. As the traditional harmonic foundation weakened—partly because the enlarged timescale makes long-term harmonic relationships hard to hear—symphonists sought new unifying techniques, among them cyclic forms, extramusical plots, progressive harmony, and so on. None of these is incompatible with dramatic sonata form, taken in its broadest sense. Nielsen retained and emphasized key conflict as a dynamic force and experimented with counterpoint and conflicting rhythms (e.g., Symphony No. 4: The Inextinguishable, 1916; and Symphony No. 5, 1922), joined movements, and the rest.

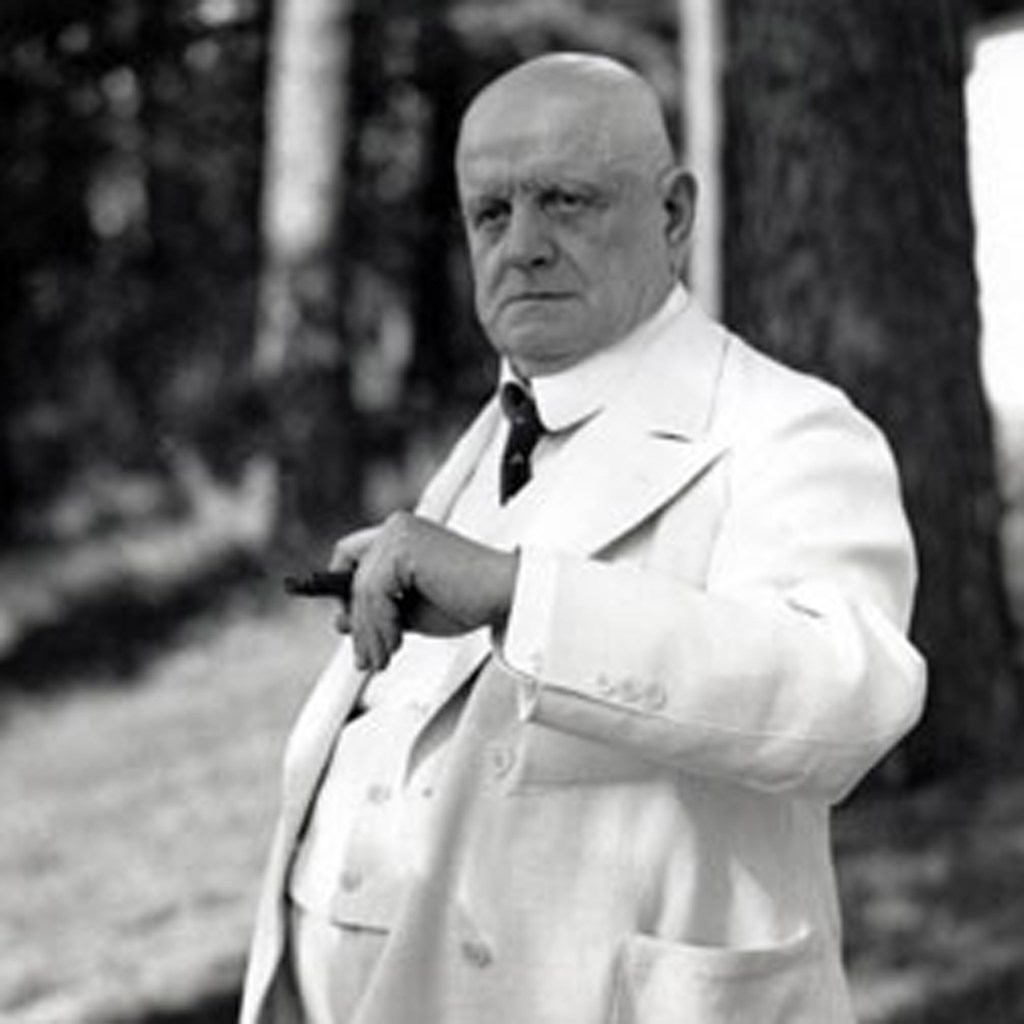

Sibelius wrote his seven symphonies between 1899 and 1925. Like Nielsen’s, they departed from Classical models (notably Beethoven’s Fifth) and reflected especially the advances of Brahms and Bruckner. Sibelius was a restrained orchestrator, a non-Wagnerian. Although nationalistic, he used no folk songs and incorporated no programs. He had little immediate influence, isolated as he was after World War I, but is highly regarded presently in his native country, and in England and the United States. Sibelius, like Nielsen, is not tied to Classical tonic-dominant opposition. He sometimes introduces modal scales and polar harmonic goals between which the music oscillates. A chief unifying device is a repeated bass line or sustained pedal point. His themes are often groups of melodic fragments, meaningless when out of context, that are capable of being combined in various ways. The gradual integration of these motives is an important means of development. In this Sibelius resembles Borodin; the effect is quite unlike that of Mahler’s long melodies. Structurally Sibelius is terse and simple. He eliminated transitions and introductions, avoided simple recapitulation, and kept harmonies static or ambiguous over long stretches. Rarely was he merely playful. He was fond of low, dark sounds. Sibelius is hardly unemotional but certainly is not effusively romantic. His symphonies represent a great contrast with Mahler’s, and he strikes a new path away from the sonata.

Source: Britannica

Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Opus 39

First version 1899:

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Scherzo

4. Finale (quasi una fantasia);

first performance in Helsinki, 26th April 1899 (Orchestra of the Helsinki Philharmonic Society under Jean Sibelius).

Final version 1900:

1. Andante ma non troppo - Allegro energico

2. Andante (ma non troppo lento)

3. Scherzo (allegro)

4. Finale (quasi una fantasia):

first performance in Helsinki, 1st July 1900 (Orchestra of the Helsinki Philharmonic Society under Robert Kajanus).

Sibelius started to plan his first symphony in the spring of 1898 in Berlin. The first plan, for "a musical dialogue", included a programmatic concept. Thus, the motto for the first movement would be, "A cold, cold wind is blowing from the sea." The second movement would draw its inspiration from Heine: "The pine of the North is dreaming of the palm of the South." The third movement would be "A Winter's Tale" and the fourth movement "Jorma's heaven" – a reference to Juhani Aho's novel Panu, published in 1897. This plan was not carried out, and it seems that it did not play any part in what eventually became the first symphony. However, in the same sketch book there are enthusiastic references to Berlioz, and one of the sketches marked "Berlioz?" ended up in the finale of the first symphony.

Sibelius was putting the finishing touches to his symphony in the spring of 1899, in the midst of a politically explosive situation. The "February Manifesto" issued by the Emperor of Russia aimed to restrict the autonomy of the Grand Duchy of Finland, and Sibelius reacted with several protest compositions. The Song of the Athenians was performed for the first time on 26th April 1899, at the same concert as the first symphony, which was initially called Symphony in E minor, or Symphony in four movements.

The Song of the Athenians aroused the public to a peak of enthusiasm, but of course the critics also paid attention to the symphony. "The greatest creation that has originated from Sibelius's pen", wrote Oskar Merikanto in Päivälehti.

Sibelius himself was not entirely pleased with his symphony, the original version of which is not known. He revised the work in the spring and summer of 1900 for the European tour of the orchestra of his friend, Robert Kajanus. The atmosphere was gloomy, since the Sibeliuses' third daughter, Kirsti, had died of an illness. She was just over a year old, and Aino had become ill from mourning the loss of her child.

Nevertheless, the revision proved useful. During the tour, in the summer of 1900, the first symphony became the work with which Sibelius achieved his international breakthrough. It was acclaimed by the critics in Stockholm, Copenhagen, Hamburg, Berlin and - to a lesser extent - in Paris. The work was found to be Tchaikovskyan, but above all people heard in it the voice of a fascinating new composer: "His symphony, a work full of unrestrained strength, full of passionate vivacity and astonishing audacity is – to state the matter plainly – a remarkable work, one that steps out on new paths, or rather rushes forward like an intoxicated god," wrote Ferdinand Pfol in Hamburger Nachrichten.

The beginning of the work is one of the most original in the history of the symphony. A solitary clarinet solo breathes a sense of desolation, which is from time to time emphasised by the distant rumbling of the timpani in the opening section, Andante, ma non troppo.

Source: Sibelius

Symphony No. 4 in A Minor, Opus 63

1. Tempo molto moderato, quasi adagio

2. Allegro molto vivace

3. Il tempo largo

4. Allegro.

Completed in 1911; first performance in Helsinki on 3rd April 1911 (Orchestra of Helsinki Philharmonic Society under Jean Sibelius).

The fourth symphony was once considered to be the strangest of Sibelius’s symphonies, but today it is regarded as one of the peaks of his output. It has a density of expression, a chamber music-like transparency and a mastery of counterpoint that make it one of the most impressive manifestations of modernity from the period when it was written.

Sibelius had thoughts of a change of style while he was in Berlin in 1909. These ideas were still in his mind when he joined the artist Eero Järnefelt for a trip to Koli, the emblematic “Finnish mountain” in Karelia, close to Joensuu. The landscape of Koli was for Järnefelt an endless source of inspiration, and Sibelius said that he was going to listen to the “sighing of the winds and the roar of the storms”. Indeed, the composer regarded his visit to Koli as one of the greatest experiences of his life. “Plans. La Montagne,” he wrote in his diary on 27th September 1909.

The following year Sibelius was again travelling in Karelia, in Vyborg and Imatra, now acting as a guide to his friend and sponsor Rosa Newmarch. Newmarch later recollected how Sibelius eagerly strained his ears to hear the pedal points in the roar of Imatra’s famous rapids and in other natural sounds.

The trip also had other objectives. On his return Sibelius wanted to develop his skills in counterpoint, since, as he put it, “the harmony is largely dependent on the purely musical patterning, its polyphony.” His observations contained many ideas on the need for harmonic continuity. Since the orchestra lacked the pedal of the piano, Sibelius wanted to compensate for this with even more skilful orchestration.

Yet one more natural phenomenon – a storm in the south-eastern archipelago – was needed to get the symphonic work started. In addition, in November 1910 he was preparing the symphony at the same time as he was working on music for Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven, which he had promised to Aino Ackté. The Raven was never finished, but its atmosphere and sketches had an effect on the fourth symphony.

The symphony was performed for the first time on 3rd April 1911, in Helsinki. Its tone was both modern and introspective, and it confused the audience so much that the applause was subdued. “Evasive glances, shakes of the head, embarrassed or secretly ironic smiles. Not many came to the dressing room to deliver their congratulations,” Aino Sibelius recollected later. The critics, too, were at a loss. “Everything was so strange,” was how Heikki Klemetti described the atmosphere. In the years that followed audiences in many parts of the world reacted the same way.

However, Sibelius remained happy with the symphony and after the first public performance he prepared it for publication. Nowadays, the fourth symphony has come to be recognised as one of the great masterpieces of the 20th century and one of Sibelius’s most magnificent achievements. It was, after all, contemporary music of the utmost modernity, a work from which all traces of aesthetisation or artificiality had been eliminated.

A kind of motto for the work is the augmented fourth, or tritone, which creates tension in all the four movements of the symphony. The atmosphere of the work varies from joyfulness to austere expressionism. Every movement fades into silence. We are as far as we could be from the triumphant finales of the second and third symphonies.

Indeed, the fourth symphony often seems to shock listeners, and analysis of the work can turn into philosophising. It is as if Sibelius were directly penetrating the merciless core of life, laying it bare without offering any kind of false consolation. He himself had felt close to death a few years earlier, when a tumour had been removed from his throat in an operation.

The first movement is conceived in accordance with the broad principles of sonata form, but does not follow strict rules. Kai Maasalo has noted how Sibelius moved away from constructing ’sonata forms’. He adds that instead Sibelius “uses the idea of these forms: the contrast, variation and development of the themes – only the essential is left.” This means that terms such as “main theme” and “subsidiary theme” should really be put in quotation marks.

The first movement of the symphony (Tempo molto moderato, quasi adagio) begins fortissimo, with a C-D-F sharp-E progression in the low strings and the bassoon. The same notes can be found in the first movement of the third symphony, in the order C-D-E-F sharp.

Now the tritone C-F sharp becomes even more insistent. However it is not put there in order to assault the ears of conventional listeners. The tritone is here construed as part of the whole-tone scale, and the symphonic tension of the fourth symphony is largely created by the conflict between major-minor harmony and whole-tone thinking.

As a foundation for initial motif, some of the double basses maintain C as a pedal point. Could this be a recollection of the moment when the composer was trying to pick out pedal points from the Imatra rapids? Sibelius said that the beginning of the symphony should always be played as “fate, with all sentimentality excluded”.

Source: Sibelius

Leave a comment