Mishima Yukio, born Hiraoka Kimitake, January 14 1925 in Tokyo, Japan, was a prolific writer who is regarded by many critics as the most important Japanese novelist of the 20th century.

Mishima was the son of a high civil servant and attended the aristocratic Peers School in Tokyo. During World War II, having failed to qualify physically for military service, he worked in a Tokyo factory, and after the war he studied law at the University of Tokyo. In 1948–49 he worked in the banking division of the Japanese Ministry of Finance. His first novel, Kamen no kokuhaku (1949; Confessions of a Mask), is a partly autobiographical work that describes with exceptional stylistic brilliance a homosexual who must mask his sexual preferences from the society around him. The novel gained Mishima immediate acclaim, and he began to devote his full energies to writing.

He followed up his initial success with several novels whose main characters are tormented by various physical or psychological problems or who are obsessed with unattainable ideals that make everyday happiness impossible for them. Among these works are Ai no kawaki (1950; Thirst for Love), Kinjiki (1954; Forbidden Colours), and Shiosai (1954; The Sound of Waves). Kinkaku-ji (1956; The Temple of the Golden Pavilion) is the story of a troubled young acolyte at a Buddhist temple who burns down the famous building because he himself cannot attain to its beauty. Utage no ato (1960; After the Banquet) explores the twin themes of middle-aged love and corruption in Japanese politics. In addition to novels, short stories, and essays, Mishima also wrote plays in the form of the Japanese Nō drama, producing reworked and modernized versions of the traditional stories. His plays include Sado kōshaku fujin (1965; Madame de Sade) and Kindai nōgaku shu (1956; Five Modern Nōh Plays).

Mishima’s last work, Hōjō no umi (1965–70; The Sea of Fertility), is a four-volume epic that is regarded by many as his most lasting achievement. Its four separate novels—Haru no yuki (Spring Snow), Homma (Runaway Horses), Akatsuki no tera (The Temple of Dawn), and Tennin gosui (The Decay of the Angel)—are set in Japan and cover the period from about 1912 to the 1960s. Each of them depicts a different reincarnation of the same being: as a young aristocrat in 1912, as a political fanatic in the 1930s, as a Thai princess before and after World War II, and as an evil young orphan in the 1960s. These books effectively communicate Mishima’s own increasing obsession with blood, death, and suicide, his interest in self-destructive personalities, and his rejection of the sterility of modern life.

Mishima’s novels are typically Japanese in their sensuous and imaginative appreciation of natural detail, but their solid and competent plots, their probing psychological analysis, and a certain understated humour helped make them widely read in other countries.

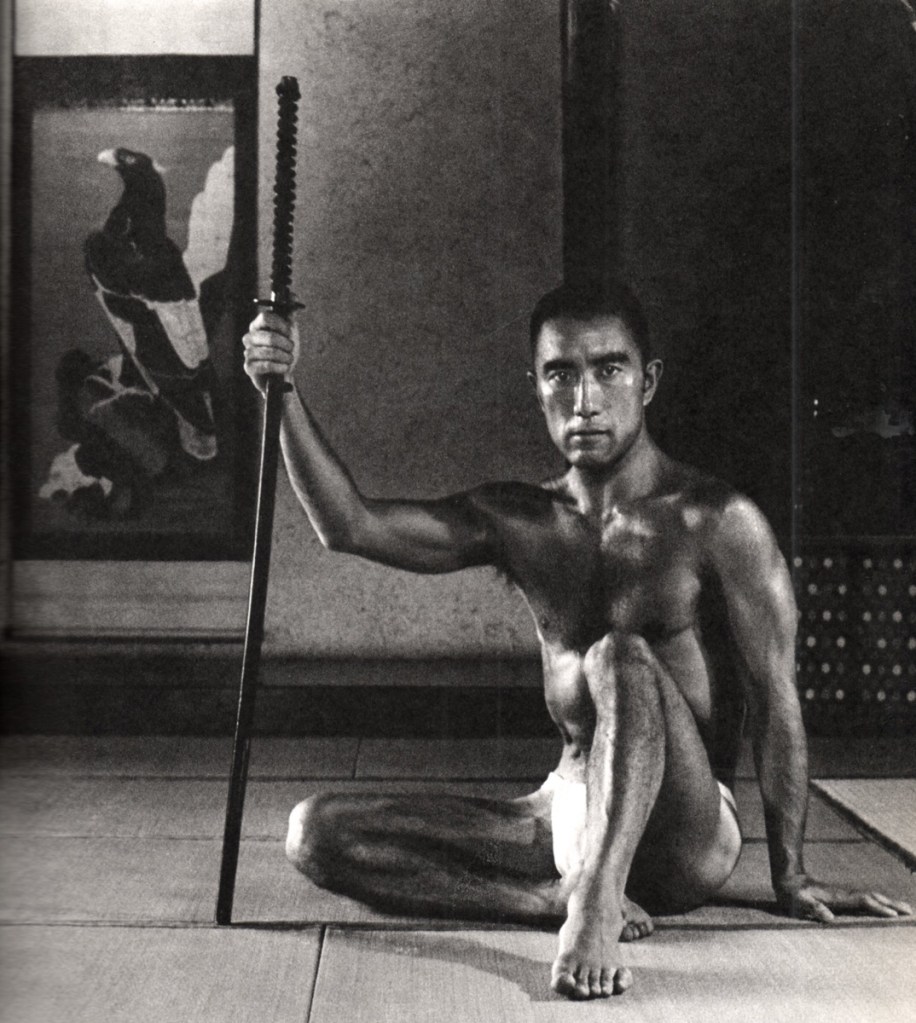

The short story “Yukoku” (“Patriotism”) from the collection Death in Midsummer, and Other Stories (1966) revealed Mishima’s own political views and proved prophetic of his own end. The story describes, with obvious admiration, a young army officer who commits seppuku, or ritual disembowelment, to demonstrate his loyalty to the Japanese emperor. Mishima was deeply attracted to the austere patriotism and martial spirit of Japan’s past, which he contrasted unfavourably to the materialistic Westernized people and the prosperous society of Japan in the postwar era. Mishima himself was torn between these differing values. Although he maintained an essentially Western lifestyle in his private life and had a vast knowledge of Western culture, he raged against Japan’s imitation of the West. He diligently developed the age-old Japanese arts of karate and kendo and formed a controversial private army of about 80 students, the Tate no Kai (Shield Society), with the aim of preserving the Japanese martial spirit and helping to protect the emperor (the symbol of Japanese culture) in case of an uprising by the left or a communist attack.

On November 25, 1970, after having that day delivered the final installment of The Sea of Fertility to his publisher, Mishima and four Shield Society followers seized control of the commanding general’s office at a military headquarters near downtown Tokyo. He gave a 10-minute speech from a balcony to a thousand assembled servicemen in which he urged them to overthrow Japan’s post-World War II constitution, which forbids war and Japanese rearmament. The soldiers’ response was unsympathetic, and Mishima then committed seppuku in the traditional manner, disemboweling himself with his sword, followed by decapitation at the hands of a follower. This shocking event aroused much speculation as to Mishima’s motives as well as regret that his death had robbed the world of such a gifted writer.

Source: Britannica

Das verratene Meer (The Betrayed Sea)

– opera in two parts and 14 scenes

Music: Hans Werner Henze

German libretto: Hans-Ulrich Treichel

Based on the novel “The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea” (Japanese: 午後の曳航, romanized: Gogo no eiko)

First Act

“Summer”: Noburu has become involved with a gang of violent minors who hate “established” society. His mother Fusako knows about this, is very worried and tries to influence her son well. She herself, a widow for eight years, wants to get married again and loves the sailor Tsukazaki. After the officer shows Fusako and Noburu, who is very impressed by everything, his ship, the boy is very proud of him. He tells the news to his friends, who don’t think much of Tsukazaki and claim that he is no different than the other adults who just forbid everything. Tsukazaki tells Noburu about his life, which was by no means always heroic. Nevertheless, Noburu, for whom Tsukazaki is a hero, now wants him to remain loyal to the sea, a symbol of space and freedom for the boys.

Second Act

“Winter”: Tsukazaki proposes to Fusako on New Year’s morning and explains that he will no longer go to sea in the future, but will help her. Noburu reports this to the gang, whose leader suggests making Tsukazaki a “hero” again. He has now familiarized himself with his future wife’s job and left the ship. The teenagers sentence Tsukazaki to death. Fusako, who later wants to hand over the business to her son and send him to Oxford as soon as possible, has no idea about this. Noburu, whose admiration for Tsukazaki and his mother has turned to hatred and contempt, lures the former sailor to the gang’s meeting place. Tsukazaki admits to giving up his job. As a result, in the eyes of the boys he has become a traitor to the sea, their idol, and is murdered by them in the back.

Source: opera guide

HANJO

composer | Toshio Hosokawa

text | Toshio Hosokawa

based on "Hanjo", a Nō play by Yukio Mishima, translated by Donald Keene

Synopsis

Once upon a time, in an inn at Nogami in Mino Province (the present Nogami in Sekigahara-cho, Fuwa-gun, Gifu Prefecture), there was a yujo* whose name was Hanago. One day, a man named Yoshida no Shōshō lodged at the inn on his way to the eastern provinces. He and Hanago fell in love and exchanged fans before his departure as the token of his promise for the future. Since then, Hanago has spent days only looking at the fan and thinking of Shōshō. Since she stopped serving at banquets, the mistress of the inn at Nogami feels disgusted at Hanago who is now nicknamed Hanjo**. Hanago is finally expelled from the inn.

On his way back from the eastern provinces, Yoshida no Shōshō visits the inn at Nogami again. He is disappointed upon learning that Hanago does not live there anymore. Shōshō with broken heart goes back to Kyoto and visits Shimogamo Shrine in the woods of Tadasu to pray. At the shrine, Hanjo, in other words Hanago, appears by accident. After being expelled from the inn, Hanago became deranged Hanjo because of her love for Shōshō and in the end reaches Kyoto.

One of the retainers of Shōshō requests that Hanjo, who prays to the deity to make her wish for love come true, entertain them by acting out her madness, and she begins to become distressed as a result of this heartless request. With the fan which she exchanged with Shōshō as a remembrance, she laments his irresponsible words and dances while expressing her loneliness. The more she waves the fan, the crazier she becomes. Hanjo discloses her love which has become more passionate when they do not meet each other. She sheds tears in distress. Shōshō who was watching the dancing Hanjo pays attention to her fan and asks her to show it. In the dusk, Shōshō and Hanago see each other’s fans and recognize that they are the lovers they looked for. The lovers are pleased by the reunion.

Source: Noh

Leave a comment