This week we celebrate the achievements of Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji, born on the 14th of August of 1892. He is one of the most enigmatic and controversial 20th century composers. Largely self-taught he chose his own way, never fitting into any school or movement. His style is highly idiosyncratic, inspired by late-romantics like Busoni and Szymanowski. Characteristic of his piano music are the enormous proportions and textural density of his works, some of them lasting several hours in performance, taxing the performer and audience to the utmost. One of these is his massive Sequentia Cyclica super Dies Irae ex Missa pro defuntis – the eight hour-plus piece for piano we will be hearing today. This work is based on the famous Gregorian chant, Dies Irae (the day of wrath) written in the 1200s, possibly much earlier. The medieval poem has been used in musical works by Giuseppe Verdi, Hector Berlioz, Benjamin Britten, Igor Stravinsky, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in their respective Requiems, as well as in other works by Thomas Adès, Ernest Bloch, Johannes Brahms, George Crumb, Charles Gounod, Joseph Haydn, Arthur Honegger, Gyorgy Ligeti, Franz Liszt, Gustav Mahler, Jules Messenet, Modest Mussorgsky, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Camille Saint/Saens, Dmitri Shostakovich, Pyotr Illych Tchaikovsky, but was also used as reference in Jethro Tull’s “Elegy”, and in literature by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Oscar Wilde. Sorabji’s work presents 27 variations, varying in length between a few minutes and more than one hour, totaling over 8 hours. It was written in 1948/49 and Sorabji regarded the work as “the climax and crown of his works for the piano and, in all probability, the last he will write”. It is impossible to describe the work in a few sentences, like all Sorabji’s works it has to be experienced in whole in order to come to terms with its vast implications and scope. Jonathan Powell, the pianist performing the piece, explains that the recording is the result of many years’ acquaintance with and preparation of this music. He is uniquely equipped to undertake the mammoth task of learning one of Sorabji’s most ambitious scores, having already given several public performances of the five-hour Opus clavicembalisticum which is, by comparison, almost a repertoire work, at least for dedicated followers of this most eccentric, quixotic, withdrawn and yet visionary of 20th-century composers. Powell began studying the piece in 2002, and performed it for the first time in 2011. Sorabji attempted to restrict performances of his music, by and large successfully, to only performers ‘with the sheer grit, determination and staying power,’ such ‘rare birds’ that they may be relied upon ‘to deduce, from internal evidence, what sort of treatment the music calls for,’ and in Jonathan Powell the composer has a worthy advocate and successor to the likes of Yonty Solomon and John Ogdon. Sorabji dedicated Sequentia Cyclica to Egon Petri, the foremost living disciple of Ferruccio Busoni, a pianist and composer highly admired by Sorabji. Busoni also provoked perplexity and extravagant praise during his lifetime – and from the opening outline of the Dies Irae chant, it becomes clear that the cycle will evolve according to the principles of Sorabji’s particular, Busoni-derived, Liszt-originated formula of intricate counterpoint and lush harmonies. As ever, Sorabji does not pretend to make the performer’s life easy, writing across six staves at some points, and leaving much of the expression to be intuited by the pianist. He regarded it, however, as ‘the climax and crown of his work for the piano.’ Its first recording, therefore, is a landmark achievement, which will be welcomed and sought after by piano literature the world over. Source: Piano Classics

Sequentia cyclica super Dies Iræ ex Missa pro defunctis, KSS 71

Written for: Piano

Date composed: 1948–49

Dedicatee: Egon Petri

Approximate duration: 500 minutes

Manuscript pages: 335

Manuscript location: Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel

Structure (duration)

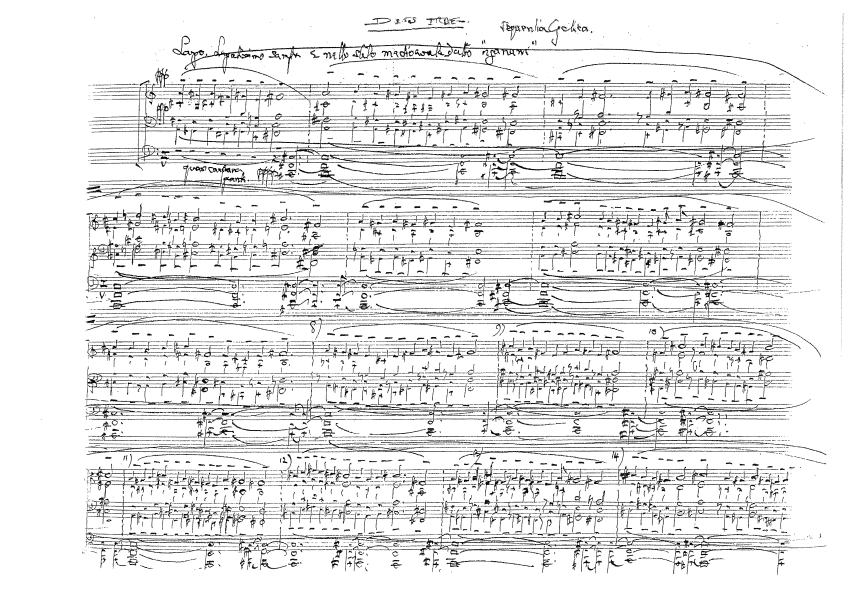

Theme – Largo Legatissimo sempre e nello stile medioevale detto ‘organum’ (4:29)

I. Vivace (spiccato assai) (7:59)

II. Moderato (8:01)

III. Legato, soave e liscio (8:30)

IV. [Tranquillo e piano] (64:45)

V. Ardito, focosamente (8:23)

VI. Vivace e leggiero (3:30)

VII. [L’istesso tempo] (2:27)

VIII. Tempo di Valzer con molta fantasia, disinvoltura e eleganza (20:54)

IX. Capriccioso (11:27)

X. Il tutto in una sonorita piena, dolce, morbida, calda e voluttuosa (33:13)

XI. Vivace e secco (2:19)

XII. Leggiero a capriccio (7:16)

XIII. Aria: Con fantasia e dolcezza (22:16)

XIV. Punta d’organo (26:48)

XV. Hispanica (13:08)

XVI. Marcia funebre (4:34)

XVII. Soave e dolce (3:24)

XVIII. Duro, irato, energico (10:27)

XIX. Quasi Debussy (7:28)

XX. Spiccato, leggiero (3:43)

XXI. Legatissimo, dolce e soave (8:49)

XXII. Passacaglia [with 100 variations] (97:31)

XXIII. Con brio (12:21)

XXIV. Oscuro, sordo (10:47)

XXV. Sotto voce, scorrevole (2:16)

XXVI. Largamente pomposo e maestoso (16:24)

XXVII. Fuga quintuplice a due, tre, quattro, cinque e sei voci ed a cinque soggetti (79:58)

– Fuga I (13:43)

– Fuga II (6:24)

– Fuga III (9:53)

– Fuga IV (8:53)

– Fuga V (41:04)