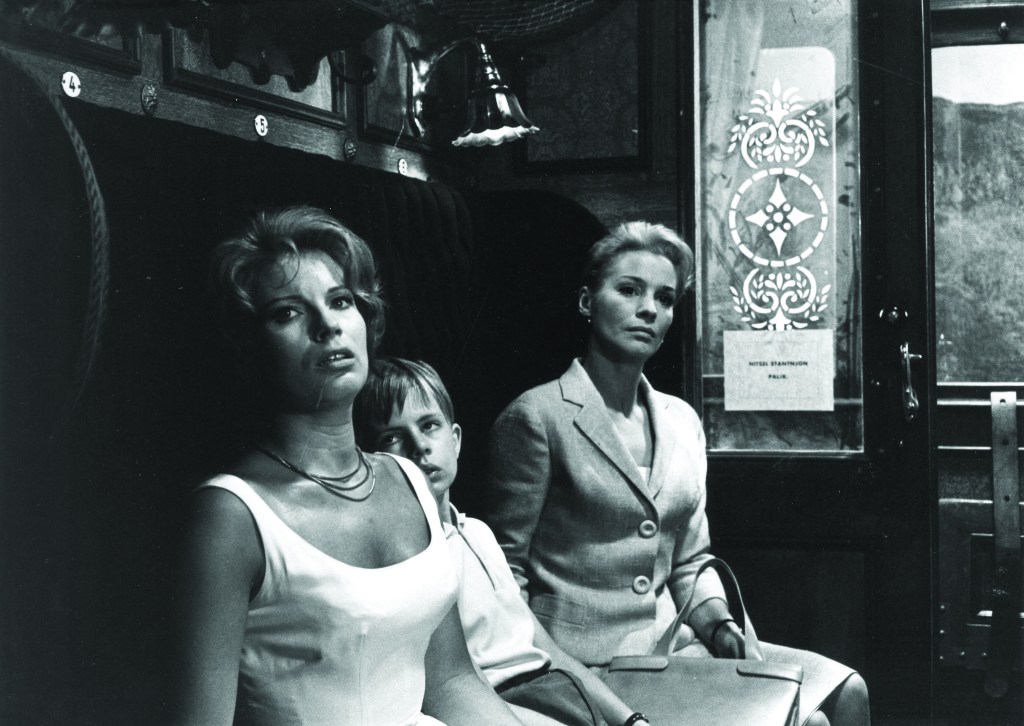

Two women, Anna and Ester, accompanied by Johan, Anna’s ten-year-old-son, travel slowly through the night by train into a foreign country that seems to be at war. They are sisters, it will turn out, perhaps lovers. We will never discover the reason for their journey, to a place where the inhabitants, the culture, and the language are unknown to them.

The Silence (1963) was originally titled God’s Silence, and it is the third in what Ingmar Bergman refers to as a trilogy, whose previous two films—Through a Glass Darkly (1961) and Winter Light (1962)—explore explicit questions of religious faith. Bergman here tries to come to terms with the pious rigidity and strangled emotional life of his own upbringing at the hands of a father who was a Lutheran clergyman and, later, court chaplain to the king of Sweden.

But both earthly and heavenly fathers are absent from The Silence, whose bleak setting is based on Bergman’s own experiences of European cities after World War II. Outside is an incomprehensible world of unreadable street signs, surging crowds, and tanks roaring in the middle of the night. Inside is a formerly grand Hotel Europa, where the three travelers have taken rooms.

The Silence is in part a prelude to later films, in which Bergman has shifted his focus from God to people, from theology to psychology. But ideas are inert without visual expression, and it is Bergman’s genius to invite us, through extreme close-ups, to enter the mystery of people, of their faces.

The unfathomable “silence” of this city has reduced the adults in the triangle to an almost zero level of communication with the outside world. Every personal connection is oblique and truncated, creating an ominous atmosphere in which gestures and symbols are often fugitive or vaguely menacing. Bergman calls it “a rendering of hell on earth—my hell.” But this hell also mirrors what the real experience of travel can become when ignorance of language and custom provokes a helpless regression to childhood and its sometimes desperate effort to decipher meaning.

For the young and curious Johan, wandering the corridors of the strangely vacant hotel, the brooding foreign city is merely the shell of an adult world whose impenetrable emotional climate is determined by his mother and aunt. (This is made more palpable by the pervasive heat and unrelieved sweating.) As Bergman has remarked, “My impulse has nothing to do with intellect or symbolism: it has only to do with dreams and longing, with hopes and desires, with passion.”

Anna and Ester form two sides of a whole person, a theme Bergman would go on to further explore in Persona. Anna is defined almost entirely through her physicality—washing, anointing herself with perfume and lotions, getting dressed and undressed, having sex, watching others have sex. Ester, the translator, with her typewriter, paper, and pens, is instead a creature of language—suffering from the lung disease that suffocates her, masturbating, smoking, drinking, and thinking of sex as a mechanical matter of “erections and secretions” that disgust her. Her body in ruin, only words seem to keep her alive.

Amid the noise, music, and silence that layer the soundtrack, Anna and Ester are locked in a cryptic struggle that plays out before Johan’s eyes and in his feelings. As in many of Bergman’s films from this period on, the lessons of human nature are to be learned from the lives of women. Although we see many things that he does not, Johan’s perspective is the spine of the film. It is the movement of his sympathies from his seductive mother to his intellectual, ailing aunt that gives coherence and force to Bergman’s meditation on human frailty.

Source: Criterion — The Silence, by Leo Braudy, August 18 2003 (excerpts)

The Silence is one of Ingmar Bergman’s most important and most perfect films, marking a high point in his distinctive formal experimentation, challenging thematic discourse, and fomenting of radically intimate spectatorial affect.

In addition to Bergman’s developing thematic concerns, detailed and enunciated here to perfection, perhaps the clearest link to his previous work is the commanding central performances by Ingrid Thulin (Ester) and Gunnel Lindblom (Anna). These idiomatic Bergman actors are pushed to a kind of performative and conceptual excess in The Silence. Their remarkable presence is framed and rendered via a similarly extravagant yet also very disciplined aesthetic form exhibiting both a joyous freedom of filmmaking and superb structuring logic.

It is contextually and thematically important that The Silence is set in a mysterious Eastern European location, the fictional city of Timoka invented by a filmmaker from a technically “neutral” country during the Cold War. Bergman was often criticised in the 1960s for being a “non-engaged” filmmaker. But making films about a crisis-ridden modernity from the relatively safe position of a materially comfortable and peaceful state at Europe’s northern fringes provides for a different perspective, including the luxury of doubling back on its own gaze. This can be seen as played out by the apparently privileged characters, both economically (these traveling Swedes seem better off than the majority of the still part-agrarian society that is seen through the hotel window) and in their apparent ability to move through a divided Europe with ease while also seeming to have no real knowledge of its more “othered” realms. While this marks such figures, and Bergman, as bewildered by an alien reality as bunkered away in their hotel, they are, more broadly, varyingly self-conscious participants in – and expressions of – the psychological, moral and philosophical crisis that a fragmenting European culture (itself with increasingly “alien” characteristics) brings about.

As with Bergman’s masterly 1968 film Skammen/The Shame, where war is monstrous in large part because driven by politics that are absurd in their impenetrability (akin to metaphysical belief), there is no explanation for war in The Silence beyond the presumed – itself frequently absurd – Cold War opposition. When Johan (Jörgen Lindström) sees tanks and artillery through the train window in the film’s remarkable first scene and later a lone tank as it mysteriously rolls into the street outside the hotel, such machines appear as menacingly inexplicable objects without political explanation or justification.

Despite its formal elements resulting in Bergman’s most elusive and confusing work to date, The Silence is often seen as completing a trilogy around the notion of faith along with the preceding Såsom i en spegel/Through a Glass Darkly (1961) and Nattvardsgästerna/Winter Light (1963), in which the tenuous humanism of the first film (the very unconvincing “God is Love” lecture by the father at the end) and the ambiguous continuation of faith through ritual in the second film (the show must go on in the interests of its performative adherents, a country priest and his small flock), is “answered” with the more overt nihilism of the third. However, to see it purely as thematically completing a trilogy in this way denudes the film of much of its complexity and potential resonance – or, alternatively, we can look back on the “faith” theme in the other films as not just concerning religious belief but figuratively addressing modernity’s displacements as well. By not explicitly addressing theological issues, The Silence allows much greater room than its immediate predecessors for secular regimes to come under the microscope – in particular here, setting the tone for the remainder of Bergman’s remarkable ‘60s cinema, the very notion of the human subject itself. And of particular note is that with this film we are, for the first time, without a central male subject or patriarch.

The only “men” in the film are the young Johan, the waiter (a wordless sex object, the film reversing the usual gender dynamics by having Anna pick him up), and the very old hotel porter. The character whose role comes closest to that of a patriarch, or a figure continuing the traditions and values thereof, is Ester. This is highlighted by her articulation of intellectual and moral virtues, a perspective that she holds as essential in large part because it is handed down from the culture she associates with her father. But she is clearly dying. Though Bergman’s treatment of women onscreen can be endlessly debated, the lack of patriarchal power in The Silence is another case in which we can see his work as perhaps more politically interesting than is often assumed, albeit on an unusually abstract conceptual (and skeptically framed) level.

Without any role model to speak of, Johan is free – whether he likes it or not – to roam a seemingly absurd world suggested by the decayed grandeur and strange occupants of the hotel and the threatening present-day reality outside. It is in this context, perhaps, that we can best approach a cliché here (thanks to Fellini) of ‘50s and ‘60s art cinema, the boy’s encounter with a “troupe of Dwarves”. On one level at least, this is a joyous episode of potential polymorphous delights where Johan is put into a dress after pretending to shoot one of the diminutive cabaret performers he spies through the door of a room and prompting a spontaneous party. That is, until a father figure intervenes and reasserts the Symbolic order of the day, after which he is politely ushered out while his new friends are reprimanded for their decadence. Following this brush with anarchic pleasure and its hierarchical gender-asserting curtailment, Johan surreptitiously pisses in the corridor of the hotel.

Two further scenes add substantial words to the film’s image and sound-reliant composition and structure. Both feature amongst Bergman’s best ever writing, perfectly complimenting (never overwhelming) the aesthetic and performative layers, as bodies and faces are constantly repositioned in space. The dramatic high-point is a climactic argument between the two women after Ester finds the hotel room in which Anna is in the midst of post-coital torpor with the waiter from the street bar. This argument addresses more explicitly the central tension or implacable opposition between the two – broadly, whether one’s life and efforts should be seen as meaningful, morally and intellectually. (Anna accuses Ester of always going on about “how important everything is”, to which she replies: “but how else are we to live?”) Topping this is Ester’s bed-ridden monologue very late in the film. Though we might assume immanent demise (her condition is worsening, and Anna and Johan are about to catch the train back home without her), in this remarkable scene Ester self-consciously performs the figurative death of her grounding investments and raison d’etre. Linguistically and existentially alone in bed, with only the uncomprehending wrinkled porter by her side, she tries to write Johan a “letter” to take with him entitled “Words in the foreign language”, when her body erupts into seeming death spasms. As they momentarily subside, Ester appears to confront the brute truth of her embodied reality (and its inevitable fate). Sitting up in a hunched position and pulling back sweaty limp hair, she says with calm clarity and spite: “It’s all just erectile tissue and secretion”, while reaching disgustedly at her armpit and breast. Then, with exhausted hatred: “Semen smells nasty to me… I stank like a rotten fish when I was fertilized.” Collapsing back onto the bed and clasping the top of the old man’s head, staring death in the face, she more soberly describes her delusions in a truly Bergmanesque lament: “I wouldn’t accept my wretched role…. We try out attitudes, and find them all worthless. The forces are too strong. I mean the forces… the horrible forces,” before an even worse convulsion hits.

Source: The Silence / Sense of Cinema, Hamish Ford

Cast/Credits

Director: Ingmar Bergman

Writer: Ingmar Bergman

Starring: Ingrid Thulin, Gunnel Lindblom, Birger Malmsten, Håkan Jahnberg, Jörgen Lindström

Cinematography: Sven Nykvist

Release date: 23 September 1963

Running time: 105 minutes

Country: Sweden

Language: Swedish

Leave a comment