Please, bear with me as I repeat something I must repeat.

While living in the lively and artistic city of Liège, Belgium, (1995-2000) swimming, soaring and diving into questions and thoughts on what it means to be a human, and furthering artistic concepts around the topic of the process of dying, one conclusion appeared with clarity to me. If responsible and gifted, an individual has a social and existential function to live by: to live in such a way that even postmortem fruit may be bore, in clarity, inspiration or guidance for those who continue to live.

Dozens of artists came to mind which, while still alive, seemed forgotten after their immense contributions had moved millions for decades. The desire was then born to make a list of those, alive or not that I consider worth of remembering more often, whenever possible, and, before their passing. Decades later, and no longer living in Europe, being a contributor to the Clubhouse community became the first opportunity to apply this thought, by making rooms with which to celebrate such individuals.

Familiar with his name but knowing nothing about his work, a year ago I opened a room dedicated to Ingmar Bergman. Presenting that room made me curiously hungry for knowing about his person and work. Subsequently I began to watch his films. A year later, I have watched about one third of the works he produced for the cinema, and feel moved, having the opportunity to once again celebrate him, though, this time with a bit of understanding for his work and contributions.

These birthday celebrations serve two main goals: enable a deeper dive into the importance of individuals and their body of work, and paying tribute, simply by remembering. And through Days with Ingmar Bergman I intend to celebrate and learn, precisely, grateful for those who come, listen, and share their Bergman impressions.

My interest for the cinema is generally not based on formal training and practical experience that I might be equipped enough in expressing a profound analysis of his oeuvre as reliable written source. For this reason I have chosen articles that do that below.

In appreciation for his contributions, a celebration of his life will be presented at the houses Animal Noble, and La Vida en Blanco y Negro (in Spanish) on Clubhouse, to which you are herewith cordially invited.

Ingmar Bergman Preliminaries

a general conversation about his importance in the world of cinema, and in preparation for the following week, during which a daily room is scheduled to discuss six of his films.

July 3rd, at 11 am EST

in Animal Noble (English)

July 3rd, at 3 pm EST

en La Vida en Blanco y Negro (Español)

— on Clubhouse —

Days with Ingmar Bergman

Animal Noble

Sunday, July 9th, at 11 am EST – The Silence – 1963

Monday, July 10th at 11 am EST – Persona – 1966

Tuesday, July 11th, at 11 am EST – Cries and Whispers – 1972

Wednesday, July 12th, at 11 am EST – Through a Glass Darkly – 1961

Thursday, July 13th, at 11 am EST – Scenes from a Marriage – 1973

Friday, July 14th, at 11 am EST – Autumn Sonata – 1978

La Vida en Blanco y Negro

Viernes, Julio 14, a las 3 pm EST – Ingmar Bergman, Autor

Ingmar Bergman

Filmmaker, Theater Director, Author

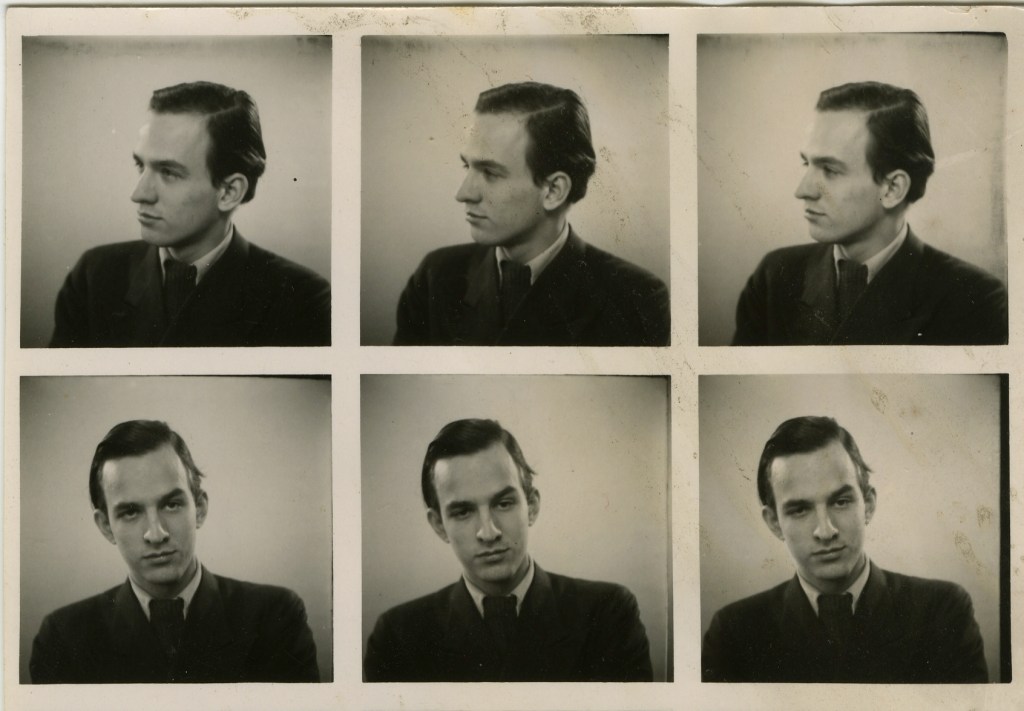

Photo source: Ingmar Bergman

Ingmar Bergman, born Ernst Ingmar Bergman, July 14, 1918, in Uppsala, Sweden, is the film writer and director who achieved world fame with his films, and is noted for his versatile camerawork and for his fragmented narrative style, which contribute to his bleak depiction of human loneliness, vulnerability, and torment.

Bergman was the son of a Lutheran pastor and frequently remarked on the importance of his childhood background in the development of his ideas and moral preoccupations. Even when the context of his film characters’ sufferings is not overtly religious, they are always implicitly engaged in a search for moral standards of judgment, a rigorous examination of action and motive, in terms of good and bad, right and wrong, which seems particularly appropriate to someone brought up in a strictly religious home. Another important influence in his childhood was the religious art Bergman encountered, particularly the primitive yet graphic representations of Bible stories and parables found in rustic Swedish churches, which fascinated him and gave him a vital interest in the visual presentation of ideas, especially the idea of evil as embodied in the Devil.

Bergman attended Stockholm University, where he studied art, history, and literature. There for the first time he became passionately involved in the theatre and began writing and acting in plays and directing student productions. From these he went on to become a trainee director at the Mäster Olofsgärden Theatre and the Sagas Theatre, where in 1941 he produced a spectacularly unconventional and disastrous production of the Swedish playwright August Strindberg’s The Ghost Sonata. In 1944 he was given his first full-time job as a director, at Helsingborg’s municipal theatre. Also, and more importantly, he met Carl-Anders Dymling, the head of the Svensk Filmindustri. Dymling was sufficiently impressed by him to commission an original screenplay, Hets (1944; Frenzy, or Torment). This was directed by Alf Sjöberg, then Sweden’s leading film director, and was an enormous success, both at home and abroad. Largely as a result of this success, Bergman was, in 1945, given a chance to write and direct a film of his own, Kris (1946; Crisis), and from this point on his career was under way.

The films that Bergman wrote or directed, or both, in the next five years were, if not directly autobiographical, at least very much concerned with the sort of problems that he himself was encountering at that time: the role of the young in a changing society, ill-fated young love, and military service. At the end of 1948 he directed his first film based on an original screenplay of his own, Fängelse (1949; Prison, or The Devil’s Wanton). It recapitulated all the themes of his previous films in a complex, perhaps overambitious story, built around the romantic and professional problems of a young film director who considers making a film based on the idea that the Devil rules the world. While this is not to be taken without qualification as Bergman’s message in his early work, it may at least be said that his imaginative world is divided very sharply between the worlds of good and evil, the latter always overshadowing the former, the Devil lying in wait at the end of each idyll.

Bergman acquired a country home on the bleak island of Fårö, Sweden, and the island provided a characteristic stage for the dramas of a whole series of films that included Persona (1966), Vargtimmen (1968; Hour of the Wolf), Skammen (1968; Shame), and En passion (1969; A Passion, or The Passion of Anna), all dramas of inner conflicts involving a small, closely knit group of characters. With The Touch (1971; Beröringen), his first English-language film, Bergman returned to an urban setting and more romantic subject matter, though fundamentally the characters in the film’s marital triangle are no less mixed up than any in the Fårö cycle of films. And then Viskningar och rop (1972; Cries and Whispers), Scener ur ett äktenskap (1974; Scenes from a Marriage), and Höstsonaten (1978; Autumn Sonata), all dealing compassionately with intimate family relationships, won popular as well as critical fame.

Through the years, Bergman continued to direct for the stage, most notably at Stockholm’s Royal Dramatic Theatre. In 1977 he received the Swedish Academy of Letters Great Gold Medal, and in the following year the Swedish Film Institute established a prize for excellence in filmmaking in his name. Fanny och Alexander (1982; Fanny and Alexander), in which the fortunes and misfortunes of a wealthy theatrical family in turn-of-the-century Sweden are portrayed through the eyes of a young boy, earned an Academy Award for best foreign film. In 1991 Bergman received the Japan Art Association’s Praemium Imperiale prize for theatre/film.

Bergman also directed a number of television movies, notably the critically acclaimed Saraband (2003), which featured the main characters from Scenes from a Marriage, and the movie received a theatrical release. In addition, he wrote several novels, including Söndagsbarn (1993; Sunday’s Children) and Enskilda samtal (1996; Private Confessions), that were made into films. His memoir, Laterna magica (The Magic Lantern), was published in 1987.

Source: Britannica

Bergman, the master of world cinema who delved deep into our souls

Over a 60-year career as either writer or director and usually as both, Ingmar Bergman, the Swedish filmmaker who died Monday, created a body of work that’s unmistakable and unique in its depiction of the soul’s inner struggle. Using a medium that records surfaces, he captured the private, the elemental, the unspoken longings and shattering terrors that define the real experience of life on this planet. And he did so with more raw intensity and uncluttered truth than any filmmaker before or since.

Bergman was a towering, unsurpassed figure in world cinema and one of the dominant and defining artists of the 20th century. His pursuit of truth was unyielding and lifelong. From his first film to his last, he saw life as a series of mysterious circumstances, and he would not yield to any facile attempt to define it. Instead, he used his camera to record the nature of that mystery, by cutting through the clutter of hope, worry and ego to perceive life as it is.

His fascination was, as he put it, “the wholeness inside every human being,” and his subjects were love, death, God, lust, emotional alienation and cruelty – basic emotions and concerns that give the lie to the pervasive impression of Bergman as a cerebral, austere filmmaker.

He was born July 14, 1918, the son of a Lutheran minister to the court of Sweden and a wealthy mother. Bergman’s observations of the tensions and infidelities within his parents’ marriage would make a lifelong impression and form the basis for many of the relationships depicted in his films.

Though he insisted he was never a bookworm, he studied literature and art at the University of Stockholm. His goal was to be a stage director, and in 1944 he became the manager of the Halsingborg City Theater. For the next 20 years, even as film dominated his life, Bergman would always maintain his connection with the stage, working in theaters throughout Sweden. It was through the stage that Bergman found most of the remarkable actors that would form his cinematic stock company: Erland Josephson, Harriet Andersson, Ingrid Thulin, Max von Sydow, Liv Ullmann, Gunnar Bjornstrand, Bibi Andersson and others.

He wrote the screenplay to an Alf Sjoberg film, “Frenzy,” in 1944; and his film career was launched. In 1946, he became a director with the film, “Crisis,” and over the next seven years developed and honed his skills as a filmmaker, directing nine films and writing several more. In 1953, he directed a free-spirited Harriet Andersson in “Summer With Monika,” about the complications that ensue when two young people fall in love and the girl becomes pregnant. The shot of Andersson on an incline in the midst of nature, as seen from below with her blouse half undone, became an iconic image of the new European cinema.

But it was with “Smiles of a Summer Night” (1955), a romantic comedy, that Bergman first came to international attention. Two years later, “The Seventh Seal” (1957), in which a medieval knight (von Sydow) plays chess with death, introduced the filmmaker in a darker, more questing vein, while providing one of the classic tableaux of Bergman’s oeuvre. “Wild Strawberries,” released later that year, received widespread acclaim, with its story of an old man’s (Victor Sjostrom) journey of discovery, as he comes to grips with his personal failings, in anticipation of death.

During the early ’60s, Bergman made three chamber films, each dealing with the issue of faith, and each requiring performances of profound emotional intimacy. In “Through a Glass Darkly” (1961), which won the Academy Award for best foreign film, Bergman traces the descent of a lively young woman (Harriet Andersson) into mental illness. The solo moments, in which Andersson retreats into a room to commune with the spirits in her mind, are staggering in their emotional nakedness. In “Winter Light” (1962), Bergman told the story of a Lutheran priest (Bjornstrand), who tries, without success, to dissuade a depressed man (von Sydow) from killing himself. The last film in the faith trilogy, “The Silence,” created a stir in 1963 for its use of nudity and its presentation of raw carnality.

Bergman’s austerity was only on the surface. His films were about little besides emotion, and his focused commitment to depicting emotion made his films more truly passionate than even those of his Italian contemporary, Fellini.

“No form of art goes beyond ordinary consciousness as film does, straight to our emotions, deep into the twilight of the soul,” he once wrote. Beginning with the faith trilogy and for the rest of his career, Bergman worked to create a cinema that consisted entirely of such moments of deep psychological penetration.

Other directors might settle for less. Other filmmakers might guide an audience through an entire story just to arrive at some special moment of intensity or revelation. Bergman found such achievements too small for his talents. Other directors might entertain an audience through plot just to arrive at some golden moment of meaning.

Bergman strived to make films that were all meaning, that revealed themselves and kept revealing themselves, peeling away layer after layer, and finding a deeper truth. In that sense, “Cries and Whispers” (1972), about two sisters who gather around the death bed of a third sister, can be seen as Bergman’s apotheosis.

Having put away metaphysics with the faith trilogy, Bergman entered his great period with “Persona,” about an actress who can no longer speak (Ullmann) and a talkative nurse (Bibi Andersson), with whom she develops an intense and tortured relationship. The film, about emotional vampirism and identity, contains one of the most famous images in 20th century film: Andersson and Ullmann looking directly into the camera, their faces pressed together. “Hour of the Wolf” (1968) continued in this psychological vein, with von Sydow as a man struggling with his sanity.

“Shame” (1968), about the effect of civil war on two artists (von Sydow and Ullmann), was Bergman’s artistic response to the Vietnam War. His strategy was simple but brilliant: He showed westerners going through what the average Vietnamese citizen was going through – terror, anxiety, degradation and confusion.

“Cries and Whispers” was nominated for a best picture Academy Award but lost to “The Sting.” The following year Bergman created one of his most accessible and popular works, “Scenes from a Marriage” (1974), starring Ullmann and Josephson as a suburban married couple with deep resentments boiling beneath the surface.

In 1976, Bergman was arrested by Swedish authorities for income tax fraud and suffered a nervous breakdown. He left Sweden and moved to Munich, where he directed for the stage and made films, including his masterful mother-daughter study, “Autumn Sonata” (1978), starring Ingrid Bergman (in her last film performance) and Ullmann.

The charges against Bergman were dropped, and he returned to Sweden in 1981 to film the autobiographical “Fanny and Alexander” (1983), which became his greatest international hit. Upon its completion, the 65-year-old director announced it would be his final film. But like that great retiree, Frank Sinatra, Bergman found himself surprised by longevity, and over the next 20 years, he continued to work. He directed for the stage and provided the screenplays for a number of films, most notably for “Faithless” (2000), a semi-autobiographical film about adultery, directed by Ullmann.

Bergman’s vision, which once shocked audiences by showing the passion underneath the facade of repression, now seemed reassuring in at least one regard. Rare among 21st century artists, Bergman still believed in human complexity and value. He believed that the actions of people mattered. Finally, in 2003, Bergman, still enjoying good health, did the inevitable – he went back to directing, with “Saraband.” Starring Ullmann and Josephson, the film took the characters they’d played in “Scenes from a Marriage” and told the story of the ensuing 30 years. The master had lost none of his fire.

Like Virginia Woolf and James Joyce in literature, Ingmar Bergman strove to capture and illuminate the mystery, ecstasy and fullness of life, by concentrating on individual consciousness and essential moments. His achievement is unsurpassed. He is one of the few filmmakers who can be spoken of in the same breath with those artists and with other supreme figures of other disciplines.

Bergman was and always will be at the pinnacle.

By Mick LaSalle, Chronicle Movie Critic, July 31, 2007 / Source: SFGATE

Major Works

- Kris (1945; Crisis)

- Skepp till Indialand (1947; A Ship to India, or The Land of Desire)

- Hamnstad (1948; Port of Call)

- Fängelse (1949; Prison, or The Devil’s Wanton)

- Törst (1949; Thirst, or Three Strange Loves)

- Till glädje (1949; To Joy)

- Sommarlek (1951; Illicit Interlude, or Summer Interlude)

- Kvinnors väntan (1952; Secrets of Women, or Waiting Women)

- Gycklarnas afton (1953; The Naked Night, or Sawdust and Tinsel)

- En lektion i kärlek (1954; A Lesson in Love)

- Kvinnodröm (1955; Dreams, or Journey into Autumn)

- Sommarnattens leende (1955; Smiles of a Summer Night)

- Det sjunde inseglet (1957; The Seventh Seal)

- Smultronstället (1957; Wild Strawberries)

- Nära livet (1958; Brink of Life, or So Close to Life)

- Ansiktet (1958; The Magician, or The Face)

- Jungfrukällan (1960; The Virgin Spring)

- Djävulens öga (1960; The Devil’s Eye)

- Såsom i en spegel (1961; Through a Glass Darkly)

- Nattsvardsgästerna (1961; Winter Light)

- Tystnaden (1963; The Silence)

- För att inte tala om alla dessa kvinnor (1964; All These Women, or Now About These Women)

- Persona (1966)

- Vargtimmen (1968; Hour of the Wolf)

- Skammen (1968; Shame)

- En passion (1969; The Passion of Anna)

- Beröringen (1971; The Touch)

- Viskingar och rop (1972; Cries and Whispers)

- Scener ur ett aktenskap (1974; Scenes from a Marriage)

- Trollflojten (1974; The Magic Flute)

- The Serpent’s Egg (1977)

- Herbstsonate (1978; Autumn Sonata)

- From the Life of the Marionettes (1980)

- Fanny och Alexander (1983; Fanny and Alexander)

Source: Britannica

3. Retratos sin rostros 3.1. Vacuidad tras la m‡scara Si ya Bertholt Brecht afirmaba en 1931 que Òlos nuevos aparatos fotogr‡ficos ya no componen los rostrosÓ, puesto que fijan con nitidez el instante fugaz de la toma, tambiŽn se cuestiona si en verdad es necesaria su composición e intuye que es posible Òun nuevo modo de fotografiar, accesible a los nuevos aparatos, que descompone los rostrosÓ (Benjamin, 2007, p. 120). El dramaturgo alem‡n parece anticiparse con estas palabras a los principios que ocupar‡n la cinematograf’a del director sueco a partir de los a–os cincuenta, llegando al apogeo de su complejidad con los retratos nihilistas realizados durante las dŽcadas de los sesenta y setenta. El verdadero rostro, si es que hay tal rostro, se oculta una y otra vez bajo una infinitud de l‡minas. Capa sobre capa, m‡scara sobre m‡scara, parece imposible llegar al fondo del precipicio. En El Rostro (Ansiktet, 1958), Bergman ilustra lœcidamente el conflicto entre el idealismo, que promete la existencia de algo m‡s all‡ de lo visible, y el racionalismo, que lo desmiente como patra–a quimŽrica. Max von Sydow, irreconocible al caracterizarse como una especie de figura de cera, interpreta al mago e hipnotizador Vogler. A mediados del siglo XIX Vogler llega a Estocolmo para realizar un espect‡culo ilusionista, sin embargo, el misterioso disfraz y sus fant‡sticas habilidades despiertan la curiosidad del comitŽ cient’fico encabezado por el escŽptico doctor VergŽrus (Gunnar Bjšrnstrand), quien trata de comprender el cuerpo como objeto, como soporte material que configura la imagen del hombre. El mago se ve sometido a un agresivo an‡lisis fisiol—gico que pretende desmentir la ilusi—n inexplicable que tiene lugar ante sus ojos, pero personaje y persona, realidad e fantas’a se confunden en la figura del protagonista, que no es m‡s que su propia ficci—n. Otro personaje, un actor mediocre llamado Johan Spegel muere ante la atenta mirada de Vogler, quien ans’a descubrir en sus ojos el secreto que pertenece a la muerte, aunque su bœsqueda no encuentra una completa satisfacci—n al Òdeseo constante de experimentar reacciones y tensiones en la miradaÓ (Bergman, et al, 1966, p. 99). M‡s adelante, Spegel se aparece ante el protagonista como un fantasma, y jugando con la imagen de una linterna m‡gica dice: ÒSoy una sombra de una sombra. [É] Uno va avanzando paso a paso hacia la oscuridad pero el movimiento es la œnica verdadÓ (55Õ30Ó) (F2). Realizando una analog’a entre hombre e imagen cinematogr‡fica, Bergman muestra su convicción sobre la imposibilidad cognoscible de la identidad en el transcurso del tiempo, pues Žsta se adhiere a una superficie inestable y cambiante, en continua fuga de la aprehensión. F2. El Rostro (Ansiktet, 1958) La inexorable decadencia del cuerpo que se revela en el movimiento y la transici—n parece ser el œnico s’ntoma demostrable de la realidad. En el rostro Òhabita el sujetoÓ, y es entonces cuando el impulso de buscar el alma dentro de un cuerpo fr‡gil y corrupto -prisi—n carnal que impide liberarse a la substancia eterna y pura-, se lleva a cabo a travŽs de esta Òsuperficie liminar de tr‡nsitos tejida de orificios, de ausencias, de oquedades: boca, nariz, orejas, ojos. Ninguno de ellos es por s’ mismo, sino puro enclave de un tr‡nsitoÓ (Brea, 1991, p. 107). El cuerpo, por tanto, es un reloj de arena que advierte de la brevedad de la existencia heredera de aquel tempus fugit de Virgilio. Ahora bien, en Òla necesidad de aventajar la naturalezaÓ, como escribe Baudelaire en El pintor de la vida moderna (1863/1995, p. 102), el hombre busca detener el tiempo que afecta a su propia materia f’sica. El maquillaje juega aqu’ un papel significativo como elemento que oculta o distorsiona las cualidades del verdadero rostro, y como la m‡scara, proporciona una ficci—n inmutable a su portador. Sin embargo, este artificio encubridor de la carne desgastada -recuerdo de un tiempo ya perdido e irrecuperable- no s—lo muestra el deseo de una identidad sostenida sobre la ausencia, sino que pretende la misma ilusi—n de retenci—n temporal sobre el cuerpo que la tŽcnica fotogr‡fica ofrece sobre el material cubierto de bromuro de plata. Y si Bazin advert’a que la fotograf’a Òembalsama el tiempo; se limita a sustraerlo a su propia corrupci—nÓ (1990, p. 29), el maquillaje trata de hacer algo semejante con el rostro de aquel que anhela una estŽtica de lo est‡tico en el fluir del tiempo existencial. En cualquier caso, la ocultaci—n de las emociones tras el espesor del afeite es uno de los principales escollos a superar si se pretende completar el acto comunicativo; y por este motivo, Bergman prohib’a la utilizaci—n del maquillaje a sus actores y actrices -salvo por justificaci—n argumental-, pues s—lo as’ se puede evitar el entorpecimiento visual del verdadero rostro. As’ lo confirma Liv Ullmann en una entrevista concedida en 1980: Nunca debo usar maquillaje, ni en sus pel’culas ni en sus obras de teatro. Hay muchos beneficios en el poder mostrar lo que no se puede expresar con el maquillaje. [...] Tu cara puede ponerse p‡lida o colorada cuando sufres las emociones, en el escenario y en la vida (Wexman & Ullmann, 1980, p. 77). Cerca del delirio on’rico final de La hora del lobo (Vargtimmen, 1968), una decrŽpita mujer se deshace de su cara cubierta de un espeso maquillaje que oculta el vac’o que hay debajo (67Õ30Ó) (F3). Algo similar ocurre en otro sue–o, esta vez en Cara a cara (Ansikte mot ansikte, 1976), donde una psic—loga ÐÒanalfabeta del alma humanaÓ (Bergman, 1997, p. 15)Ð encuentra llagas y heridas sangrantes tras la piel desprendida de la cara de una de sus pacientes (72Õ05Ó) (F4). Se trata de un rostro necr—tico consumido y descompuesto en la sombra interior que produce el rostro externo, un constructo artificial erigido sobre la ausencia. Es por ello que Bergman encuentra en el rostro la tragedia de la m‡scara, que no es otra cosa que la imposibilidad de alcanzarse a s’ mismo y a los dem‡s debido a la pŽrdida de la esencia en el laberinto de la apariencia. Aumont, recuperando un tŽrmino que aparece en Los cuadernos de Malte Laurids Brigge de Rilke, denomina David V‡zquez Couto, Aparienias de la variaci—n: Fisonom’a y alegor’a en el retrato cinematogr‡fico de Ingmar Bergman. FOTOCINEMA, n¼ 12 (2016), E-ISSN: 2172-0150 149 Òutiliza procesos estŽticos espec’ficos del cine (la manipulaci—n del espacio por ejemplo) no para crear efectos intelectuales, sino para transmitir estados psico-fisiol—gicos [É] que son una parte integral de sus temas moralesÓ (1971, p. 8). Erland Josephson, uno de los actores fetiche del director sueco, dice que ÒIngmar siempre ha so–ado con una pel’cula experimental con una sola actriz Ðno actor-, y encuadrando b‡sicamente su rostro, concentrar en Žl todo el drama, sin cortes ni edici—nÓ (Llano, 2005, p. 81). Estas palabras revelan el deseo frustrado de realizar un retrato cuya imagen sea la de su duraci—n, capaz de conseguir Òla momificaci—n del cambioÓ (Bazin, 1990, p. 29) de manera ininterrumpida, y coincidiendo adem‡s con Aumont en la idea de que Òfilmar un rostro es plantearse todos los problemas del filme, todos sus problemas estŽticos, luego todos sus problemas ŽticosÓ (1998, p. 88). Sin embargo, debe entenderse la utilizaci—n de los primeros planos en la obra de Ingmar Bergman como un medio tŽcnico para profundizar en el interior del personaje, es decir, como tentativa por alcanzar la psique del hombre mediante una proximidad material con el rostro, y no de una simple experimentaci—n de la tŽcnica cinematogr‡fica, o, en el caso de la mirada a c‡mara del personaje, de un juego con la reacci—n del pœblico (Steene, 1970, p. 27). La actriz Liv Ullmann habla sobre el problema de ajustar su tŽcnica interpretativa del teatro al cine de Bergman: ÒAhora me siento m‡s c—moda en el cine. Con los primeros planos he sido capaz de encontrar una tŽcnica ’ntima que funciona muy bien para m’: el verdadero pensamiento se mostrar‡ en tus ojosÓ (Wexman & Ullmann, 1980, p. 76). Si el rostro condensa todo su cine, no es s—lo como expresi—n material de lo inmaterial, sino tambiŽn como un catalizador del mundo que lo rodea. El rostro Òcomo articulaci—n crucial, entonces, de exterioridad e interioridadÓ, en palabras de JosŽ Luis Brea (1991, p. 107), por el cual circula el sentido de lo narrado v’a primer plano. En El hombre visible (1924), el primer libro de BŽla Bal‡zs, ya aparece formulada la idea de equivalencias entre distancias f’sicas y emocionales en relaci—n al personaje/actor y al espectador/c‡mara que, en conjunci—n con David V‡zquez Couto, Aparienias de la variaci—n: Fisonom’a y alegor’a en el retrato cinematogr‡fico de Ingmar Bergman. FOTOCINEMA, n¼ 12 (2016), E-ISSN: 2172-0150 150 una persistencia en el tiempo del plano, har’a realidad la revelaci—n del alma. El escritor Pere Gimferrer, al referirse a Persona (1966) de Ingmar Bergman, parece entablar una relaci—n directa entre el espacio y el tiempo dirigido al rostro y su capacidad de abstracci—n en el medio. La simple presencia f’sica de los actores, dirigidos fŽrreamente en planos que, por su cercan’a y larga duraci—n, tienden a anular la distancia entre actor y personaje, establecer‡ con el espectador una comunicaci—n tan intensa y de una naturaleza tan peculiar que se podr‡ producir una efectiva vaporizaci—n, una especie de escamoteo, del entorno en el que los actores evolucionan (2000, p. 75). Aqu’ es posible observar cierta semejanza con el planteamiento deleuziano que explica c—mo el primer plano de un rostro no es un objeto parcial separado del conjunto al que pertenece, sino que, de acuerdo con Bal‡zs, eleva al rostro al estado de Entidad mediante la abstracci—n de las coordenadas espacio-temporales. Deleuze recupera las palabras de El film. Evoluci—n y esencia de un arte nuevo (1945), œltimo ensayo sobre teor’a f’lmica de Bal‡zs, para aclarar el origen de sus ideas en torno al primer plano del rostro como tŽcnica particular del cine capaz de descubrir la realidad. La expresi—n de un rostro aislado es un todo inteligible por s’ mismo [É]. Porque la expresi—n de un rostro y la significaci—n de esta expresi—n no tienen ninguna relaci—n o enlace con el espacio. Frente a un rostro aislado, no percibimos el espacio. [É] Ante nosotros se abre una dimensi—n de otro orden (1984, p. 142). La entidad es el afecto, lo expresado por el rostro y no el rostro mismo. En otras palabras, Deleuze afirma que con el primer plano surge de la cualidad del rostro, que es inherente a Žste, y conjuntamente forman un todo llamado icono. Por lo tanto, de un primer plano de un rostro sucede su afecto en lo que Deleuze denomina Òplano-afecci—nÓ. En este momento ocurre una separaci—n entre el rostro y su portador, una ruptura en el anclaje del rostro con sus referentes que lo a’sla despoj‡ndolo de su individuaci—n. El primer plano de un rostro es el rostro mismo, pero se trata de un rostro anulado, sin referentes, con sus funciones en suspenso. Finalmente, Deleuze explica el David V‡zquez Couto, Aparienias de la variaci—n: Fisonom’a y alegor’a en el retrato cinematogr‡fico de Ingmar Bergman. FOTOCINEMA, n¼ 12 (2016), E-ISSN: 2172-0150 151 resultado del estudio fison—mico que Bergman convierte en retrato filmado del hombre: Bergman llev— hasta su extremo el nihilismo del rostro, es decir, su relaci—n en el miedo con el vac’o o con la ausencia, el miedo del rostro frente a su nada. En toda una parte de su obra Bergman alcanza el l’mite supremo de la imagen-afecci—n, quemando el icono, consumiendo y extinguiendo el rostro (1984, pp. 143-148). Ingmar Bergman lanza una mirada descre’da hacia el interior del ser humano que se pierde en el vac’o, donde la œnica verdad es la falta de verdad y la incertidumbre se desvela en una soluci—n inadvertida que desmiente una constancia tras la apariencia cambiante.

Leave a comment