Parsifal, WWV 111

Music Drama / Opera in three acts

Composer: Richard Wagner

Libretto: Richard Wagner

Based on the 13th-century Middle High German chivalric romance Parsifal of the Minnesänger Wolfram von Eschenbach, and the Old French chivalric romance Perceval ou le Conte du Graal by Chrétien de Troyes, in the 12th century. Both tell different accounts of the Arthurian knight Parzival in his quest for the Holy Grail.

Conception: 1857 through 1882

Premiere: Bayreuth Festspielhaus, July 26 1882

Opera, Blood, and Tears

celebrates the 1882 premiere of

Richard Wagner’s Parsifal

July 26 at 3 pm EST

on Clubhouse

Synopsis

ACT I

Near the sanctuary of the Holy Grail, the old knight Gurnemanz and two sentries wake and perform their morning prayers, while other knights prepare a bath for their ailing ruler Amfortas, who suffers from an incurable wound. Suddenly, Kundry — a mysterious, ageless woman who serves as the Grail’s messenger — appears. She has brought medicine for Amfortas. The knights carry in the king. He reflects on a prophecy that speaks of his salvation by a “pure fool, enlightened by compassion,” then is borne off. When the esquires ask about Klingsor, a sorcerer who is trying to destroy the knights of the Grail, Gurnemanz tells the story of Amfortas’s wound: The Holy Grail—the cup from which Christ drank at the Last Supper—and the Spear that pierced his body on the cross were given into the care of Titurel, Amfortas’s father, who assembled a company of knights to guard the relics. Klingsor, wishing to join the brotherhood, tried to overcome his sinful thoughts by castrating himself, but the brotherhood rejected him. Seeking vengeance, he built a castle across the mountains with a magic garden full of alluring women to entrap the knights. Amfortas set out to defeat Klingsor, but was himself seduced by a terribly beautiful woman. Klingsor stole the Holy Spear from Amfortas and used it to stab him. The wound can only be healed by the innocent youth of which the prophecy has spoken. Suddenly, a swan plunges to the ground, struck dead by an arrow. The knights drag in a young man, who boasts of his archery skills. He is ashamed when Gurnemanz rebukes him, but he cannot explain his violent act or even state his name. All he remembers is his mother, Herzeleide, or “Heart’s Sorrow.” Kundry tells the youth’s history: His father died in battle, and his mother reared the boy in a forest, but now she too is dead. Gurnemanz leads the nameless youth to the banquet of the Grail, wondering if he may be the prophecy’s fulfillment.

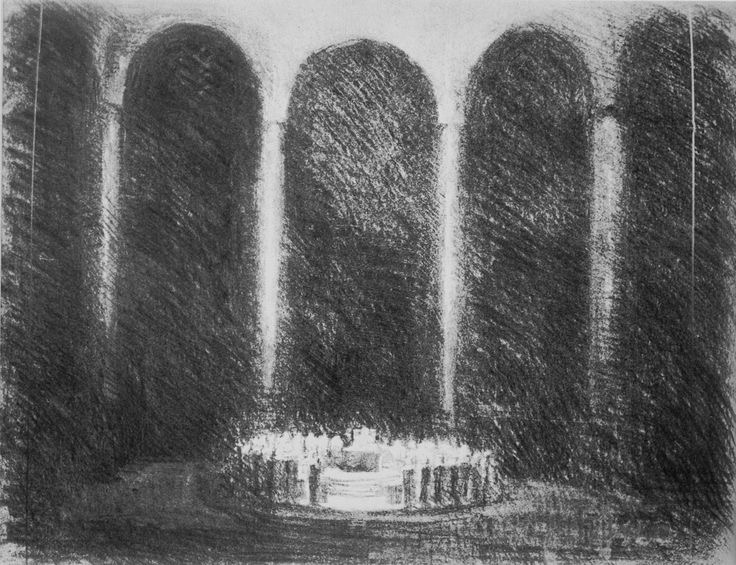

The knights assemble in the Hall of the Grail. Titurel bids Amfortas uncover the Grail to give strength to the brotherhood, but Amfortas refuses: The sight of the chalice increases his anguish. Titurel orders the esquires to proceed, and the chalice casts its glow about the hall. The nameless youth watches in astonishment but understands nothing. The ceremony ended, Gurnemanz, disappointed and angry, drives him away as an unseen voice reiterates the prophecy.

ACT II

At his bewitched fortress, Klingsor, the necromancer, summons Kundry—who, under his spell, is forced to lead a double existence—and orders her to seduce the young fool. Having secured the Spear, Klingsor now seeks to destroy the youth, whom he knows can save the knights of the Grail. Hoping for redemption from her torment, Kundry protests in vain.

The nameless youth enters Klingsor’s enchanted garden. Flower maidens beg for his love, but he resists them. The girls withdraw as Kundry, transformed into a beautiful young woman, appears and addresses him by his name—Parsifal. He realizes that his mother once called him so in a dream. Kundry begins her seduction by revealing memories of Parsifal’s childhood and finally kisses him. Parsifal suddenly feels Amfortas’s pain and understands compassion: He realizes that it was Kundry who brought about Amfortas’s downfall and that it is his mission to save the brotherhood of the Grail. Astonished at his transformation, Kundry tries to arouse Parsifal’s pity: She tells him of the curse that condemns her to lead an unending life of constantly alternating rebirths ever since she laughed at Christ on the cross. But Parsifal resists her. She curses him to wander hopelessly in search of Amfortas and the Grail and calls on Klingsor for help. The magician appears and hurls the Holy Spear at Parsifal, who miraculously catches it, causing Klingsor’s realm to perish.

ACT III

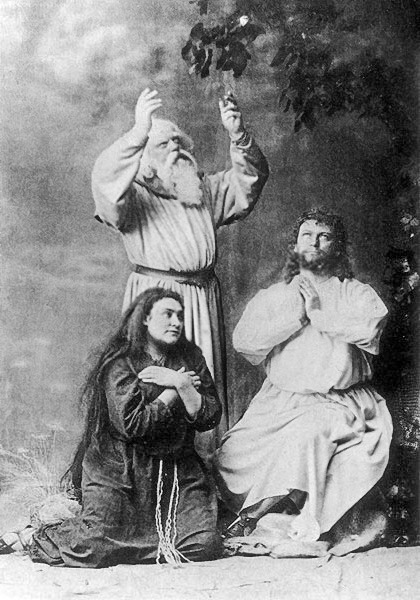

Gurnemanz, now very old and living as a hermit near the Grail’s sanctuary, finds the penitent Kundry in the forest and awakes her from a deathlike sleep. An unknown knight approaches, and Gurnemanz soon recognizes him as Parsifal, bearing the Holy Spear. Parsifal describes his years of wandering, trying to find his way back to Amfortas and the Grail. Gurnemanz tells him that he has come at the right time: Amfortas, longing for death, has refused to uncover the Grail. The brotherhood is suffering, and Titurel has died. Kundry washes Parsifal’s feet, and Gurnemanz blesses him and proclaims him king. As his first task, Parsifal baptizes Kundry. He is struck by the beauty of nature around them, and Gurnemanz explains that this is the spell of Good Friday. The distant tolling of bells announces the funeral of Titurel, and the three make their way to the sanctuary.

Knights carry the Grail, Amfortas, and Titurel’s coffin into the Hall of the Grail. Amfortas is unable to perform the rite. He begs the knights to kill him and thus end his anguish—when suddenly Parsifal appears. He touches Amfortas’s side with the Spear and heals the wound. Uncovering the Grail, he accepts the homage of the knights as their redeemer and king and blesses them. The reunion of the Grail and Spear has enlightened and rejuvenated the community.

Source: Metropolitan Opera

Review and comments by Germán A. Bravo-Casas on the book

“Wagner’s Parsifal”

By William Kinderman

Parsifal has been praised as the most inspiring music composed by Wagner as well as his most controversial composition. The hypnotic music and the depth of the plot have attracted many different audiences; the plethora of divergent views about the work continues to emerge as scholars, performers, critics and the public discover new facets in this enigmatic masterpiece, while others consider it full of ambiguities. Of all the operas composed by Wagner it is one of the longest, while its libretto is the shortest.

Completed in 1882 and premiered the same year at the Bayreuth Festival, Parsifal was the culmination of a long career; Wagner himself called it “my last card,” as Kinderman reminds us. Early in his life, Wagner was attracted to the suffering of Amfortas but the composer was apprehensive about the dramatic potential of the legend; the subject of Parsifal was in his mind for more than four decades. Wagner spent more than 30 years to complete the text, although the time devoted to the musical composition was around five years. Parsifal was conceived by Wagner to fit the acoustics of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus.

One of the principal focuses of the book is to interpret the paradoxical reception of Parsifal. In the first pages, Kinderman brings the pertinent views of the respected Wagnerian scholar Dieter Borchmeyer (President of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts): “As a rule, artists who were violently controversial in their own day sooner or later achieve classic status, no longer sparking dissent…. Wagner’s works, together with his artistic personality, continue to provoke disagreement and militate against their becoming classics” (page 6). He also quotes Michael Tanner about the paradoxical character of this masterpiece: “Difficult as it is to believe, Parsifal, Wagner’s work of peace and conciliation, has been and remains the subject of even more bitter contention than any of his other works” (ibid.)

The book is scholarly written and constitutes an expansion of many of the subjects that were succinctly presented in the 2005 Companion to Wagner’s Parsifal. The volume consists of two main parts, the process of composition, and the musical form and dramatic meaning of the work. Both parts are heralded by a Prelude called “Parsifal as Art and Ideology.” The book contains 77 musical examples, some figures, and 16 plates, including two famous illustrations by Franz Stassen (unfortunately in black and white), although it is mentioned that Oxford has created a pass-word-protected web site with color images of four of the plates that accompany the book. The jacket of the book has an attractive illustration of the young Wagner, courtesy of Naxos of America; on inquiry, Naxos said that the original is owned by Naxos Hong Kong; it is an oil canvas painted by the Chinese artist Chain Ben-Shan in 2000, on the basis of an 1865 photograph. He has made other covers for Naxos (Liszt, Beethoven, and many others). We expect that in the near future Oxford University Press will issue an affordable new paperback edition after amending some entries in the index and bibliography.

No doubt, this short but dense and expensive volume may discourage the general reader who just browses the book and notices the numerous musical examples and a lot of quotations in German, although these quotations are followed by the corresponding English translation (some of them provided by the author). Nonetheless, just a simple look at the first pages of the “Prelude” dissipates many fears. There, Kinderman reminds us about Wagner’s captivation by the legends of the Holy Grail and then traces the connections not only to Lohengrin but to other of his major works, from Die Feen (The Fairies, 1834) to the Ring. Then he shepherds us through the intricacies of the work, penetrating the details of the process of composition of the text and the genesis of the music. The delicate treatment of the various components of such a complicated work is not only rewarding, but after the reader finishes the final section of the book, titled “the sense of an ending,” realizes that the book is much more than the sum of its parts. Kinderman devotes only a few pages to the staging of Parsifal. By contrast, the Companion to Wagner’s Parsifal mentioned above, has an excellent 62-page survey written by Katherine R. Syer; it includes many of the most important productions staged up to 2002.

Jacques Derrida and other French philosophers have provided us with a particular approach called “deconstructionism” particularly to study major literary works. That approach gained a lot of attention later among theatre and opera directors, many of them branded as belonging to the Regietheater school. Here, in this book, Kinderman adopts a new approach, also of French origin, called “la critique génétique” (‘genetic criticism,’ also known in English as ‘genetic editing’). This methodology is an interdisciplinary approach that aims at “reconstructing” the sequence of actions that produced the final work of art, thus providing a new gestalt and a more comprehensive view of the entire complex work. By applying this novel methodology, Kinderman makes a reevaluation of the genesis of this important work and demolishes many traditional views about Parsifal. He finds, for example, that the highly praised analyses made by Alfred Ottokar Lorenz “through the segmentation of Wagner’s vast musical continuities into a succession of symmetrical forms,” fail to reveal “the evolving dramatic context of Wagner’s music” (page 4).

Using the critique génétique approach, Kinderman follows perfectly the scheme adopted by the Oxford series called “Studies in Musical Genesis, Structure and Interpretation.” The author sees these three components as lying on a continuum and highlights the importance of the third dimension: interpretation. Reconstructing the genesis of the work, Kinderman studies also in great detail the history of the reception of Parsifal and advises us “to beware of exaggerated interpretations, which in extreme cases collapse the artwork into a mere vehicle for religion or nationalism” (page 42). Of course, he recognizes that “music lacks defenses against ideological abuse, particularly music bound up with a ceremonial dimension, as Parsifal” (ibid).

Brilliantly, Kinderman presents the complexity of facts that made it possible for Parsifal to become a charismatic vehicle for utopian politics. He reminds us that the association of Wagner’s legacy with National Socialism began a long time before the arrival of Hitler onto the scene and that it was mainly the fanaticism of a group called the Bayreuth Circle (‘Der Bayreuther Kreis’), which identified Bayreuth as a “German thing” and viewed themselves as “Knights of the Grail.” Soon, Bayreuth became a cult and a site for a required pilgrimage. Two British-born in-laws, Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Winifred Wagner, along with Cosima, played leading roles in this transformation. Extreme nationalism and racism were then associated with Parsifal. Nevertheless, in spite of the perception of Parsifal as the gospel of National Socialism, as affirmed by Robert W. Gutman and many other authors, it is important to recognize that it was rather the Foundations of the Nineteenth Century (1899), the main book written by Chamberlain, which was considered the gospel of the Nazi movement, as acclaimed by the Völkischer Beobachter, the German Nazi newspaper. Kinderman properly reminds us that according to Chamberlain the question of race was not a central concern for Wagner and that he did not find a racist interpretation of Parsifal. Recent studies have analyzed in detail the role played by generating the myth of an Aryan race, both in India and in Germany, and Professor Dorothy M. Figueira has made an excellent treatment of the subject in her book Aryans, Jews, Brahmins (Albany, NY: New York State University Press, 2002), where she devotes a section to the role played by Chamberlain as an “Aryan publicist.” As part of the bicentennial celebrations, Professors Nicholas Vazsonyi and Julie Hubbert, from the School of Music of the University of South Carolina (Columbia, SC, USA) organized a major event called the “Wagner World Wide: America Conference” (30 January-2 February 2013), and Professor Kinderman provided an excellent 35-minute lecture, “Parsifal as Art and Ideology, 1882-1933”.

Kinderman’s account of the process of the composition of the poem is a comprehensive synthesis of the lengthy effort made by Wagner in considering and exploring a large amount of different sources; Wagner’s favourite one was Wolfram von Eschenbach’s, of which he had no less than four editions and translations in his personal library at Dresden. Of all the works composed by Wagner, there is an abundance of details about the composition of Parsifal; Kinderman reminds us that in addition to the detailed notes written by Cosima in her diaries, there are the composer’s records, and the voluminous correspondence between Wagner and his friends about this new work. The only major missing part is the abundant correspondence between Wagner and Mathilde Wesendonck, which was substantially destroyed by Cosima. It was Mathilde who introduced Wagner to the rich Spanish literature, particularly Calderón de la Barca, which gives an important role to the notions of duty, honour and valour; “my reading is, at present, confined to Calderon,” Wagner wrote to Liszt (1 January 1858). This was also a fertile period when Wagner came more interested in Indian philosophy and Buddhism, and years later, when he read Schopenhauer for the first time, he found in the German philosopher a rigorous explanation of many of the ideas that Wagner had ruminated on earlier. This was also the time when he was working on the prose sketch for his Buddhist opera Die Sieger (The Victors).

After presenting the numerous diverse events and circumstances that inspired Wagner in the writing of the poem, Kinderman asks the central question of his book: “How did Wagner successfully create ‘another main interest’ in the character of Parsifal”? And his answer is very clear and direct: “Wagner treated his Parsifal drama essentially as a type of Bildungsroman [a learning chronicle] with the education of the hero prolonged over the course of the drama” (page 60). It is the process through which, according to the Grail prophesy, “made wise through compassion the innocent fool; wait for him, the one I choose.” The key concept here, Mitleid, which unfortunately is sometimes translated as ‘pity,’ is a central subject in Indian philosophy and Schopenhauer took it from Buddhism. The original Sanskrit word Karuna refers to the ability to feel genuine and serene compassion for others; compassion helps to have full control over the fluctuations of the mind and consequently it is a powerful instrument to acquire wisdom. Undoubtedly, Wagner was familiar with these concepts, even before discovering Schopenhauer. Modern neuroscientists have found that the brain of experienced meditators produces gamma waves when they feel compassionate; gamma waves are high-frequency brain waves that lie beneath higher mental activities such as consciousness and true and unconditional love. It was that feeling of compassion that helped Parsifal not to be seduced by Kundry’s kiss and it was through compassion that the wisdom gained by the fool boy assisted him to identify his duty (his “Dharma” in the Indian tradition) and to prepare him to become the new head of the Grail community.

The author takes us through the particulars of the composition of the two prose drafts, giving particular attention to the treatment of Kundry, the most complex of all Wagnerian characters. One of the major changes made in the second manuscript is the treatment of the Holy Spear, which is used by Parsifal not as a weapon but as a healing instrument; here Kinderman reminds us that the inspiration Wagner found in the Greek legend of Telephos, where the oracle says to Achilles “He that wounded shall also heal.” By using the Holy Spear for healing, Wagner was able to connect Parsifal more easily with Amfortas and to the undisclosed prophesy disclosed by the Grail. Kinderman quotes Cosima’s famous exclamation of relief when the second draft was completed in 1877: “The Redeemer Unbound!”

In the study of the compositional genesis, which is the major contribution of this important book, Kinderman shows with particular detail the results of a dedicated delving into unfamiliar manuscripts, discovering hidden links with Wagner’s earlier works. For someone who is not a musicologist, like this reviewer, Kinderman’s book is very inspiring and motivates us to learn more, in spite of the labyrinths he pushes us to follow through the meanders of “the stress played on progressions passing through the triad to the sixth degree,” “the protracted dominant-seventh chord of A♭major,” the analyses of the “tonal pairings,” and the study of “rotational forms.”

The author reminds us that the first music that Wagner composed specifically for Parsifal was the chorus of the “Flower Maidens” in act II and says that “It is interesting that Wagner’s first music composed for Parsifal should have been associated with the United States. … the song has a decidedly saccharine flavor, which Wagner may have thought characteristic of America, since he wrote “Amerikanisch sein wollend!” (Wanting to be American!) on his sketchleaf, dated ‘9 Febr. 76,’ [the time Wagner began to work on the commissioned Grosser Festmarsch, the American Centennial March]” (page 91).

Kinderman tells us that in composing the central music for the Grail, Wagner made use of some earlier musical items, particularly the Dresden Amen and its complement, the “Faith motive,” as well as the “Communion motive” which was borrowed from the Franz Liszt cantata “The Bells of Strasburg Cathedral.” Kinderman had access to the original sketch manuscripts, many of them preserved in the Wagner Archive at Bayreuth. He analysed the original sheets containing thirty staves, as well as the inks used by Wagner in order to establish the perfect chronology of the work. The author includes in his book various bits and pieces of manuscript that Wagner cut out of his main working sheets as he thought of new musical ideas; one of the examples has a reconstructed worksheet made from five manuscript fragments. It is as if Kinderman was completing a puzzle (Plate 3 on page 86). As a result of his arduous investigation, Kinderman concludes that “the musical genesis of Parsifal, and particularly the evolution of the transformation music, reveals how Wagner sought to equate the development of music with the development of the entire drama” (page 192).

One interesting subject that has called the attention of this reader is the use of the Grail temple bells. Kinderman tells us that by March 1879, Wagner played for Cosima “the wonderful transition to the bells” (Wagner’s own words), which is “the passage leading from the Good Friday Spell to the Funeral Procession for Titurel and the change in scene to the Temple of the Grail” (page 167). This is one of the best examples of Wagner’s genius to labour with musical transitions. The Grail temple bells, outlining the fourths C-G-A-E (Do, Sol, La, Mi) are derived from the processional march and have an hypnotic character. It is interesting to mention that the carillon at the Riverside Church in Manhattan, New York, which was a gift from the late John D. Rockefeller, Jr., has a drum mechanism that automatically plays the four notes (C-G-A-E) from Parsifal’s march every 15 minutes; the bourdon bell, the largest and heaviest carillon bell ever cast, sounds the hours.

Many works about Wagner’s operas, and in particularly about Parsifal insist on the “Schopenhauerian-Buddhist influence” and do not distinguish between the two components. Today, scholars recognize that there are important differences between Buddhism and Schopenhauer and express their admiration for the skilful knowledge that Wagner had about Indian philosophy. The academic journal Wagnerspectrum,published by the Richard Wagner Museum in Bayreuth, has devoted its central section to the subject of Wagner and Buddhism with excellent articles by Pandit Bhikkhu, Dieter Borchmeyer, Wolf-Daniel Hartwich, Ulrike Kienzle, and Volker Mertens (issue 2, 2007, pages 9-113).

Paul Schofield, in his provocative book, The Redeemer Reborn. Parsifal as the Fifth Opera of Wagner’s Ring (New York: Amadeus Press, 2007), affirms that the misunderstanding of basic Buddhist teachings led Schopenhauer to a pessimistic view of human nature and to consider the denying of “the will-to-live,” as an act of renunciation, and as the only way to cease suffering. Such conclusion, affirms Schofield, is against basic Buddhist teachings. Bryan Magee concludes that Wagner “had been a Schopenhauerian in many, if uncoordinated, ways before reading Schopenhauer” and that Wagner, even before Freud, gave “the supreme importance of raising the contents of the unconscious to consciousness” (The Philosophy of Schopenhauer, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997, page 366). Among the first texts of Indian philosophy that were available in the Western world are the Bhagavad-Gita, the better known part of the Mahabharata (translated into English in 1785 by Charles Wilkins and then into French, German, and Latin), and the versions of the Rig Vedas in Latin by Friedrich August Rosen (1830) and French by Alexandre Langlois (1838-1851). It is very likely that Wagner was familiar with these texts. Hermann Brockhaus, a German Orientalist and a leading authority on Sanskrit, married Wagner’s elder sister, Ottilie in 1836 and it is known that the two exchanged views about Hinduism and Buddhism.

It is also interesting to observe that Wagner and many European philosophers of the time believed in metempsychosis, or the transmigration of souls, also referred to as the reincarnation after death. Kinderman rightly affirms that “the notion of Kundry’s many incarnations and her divided existence between the Grail and Klingsor suggests a connection to the unfinished project [Wagner’s Buddhist opera Die Sieger (The Victors)] (page 64). In the Indian tradition, it is affirmed that every action in the universe has some consequences (the law of Karma) and we have to be reborn to be purified. Referring to Kundry’s death, Kinderman asks here the critical question: “Is hers a death of redemption or an annihilation? Is it release or punishment?” (page 286).

In a puzzling note, Kinderman says that “after completing the music of Parsifal in his April 1879 drafts, Wagner’s thoughts turned yet again to loose threads in the sprawling narrative of his complete Ring: ‘Siegfried ought really to have become Parsifal and redeemed Wotan; he should have encountered the suffering Wotan (in place of Amfortas) in the course of his wanderings – but there was no augury for it, and so it had to remain as it is’ ” (page 287). This thought makes an interesting connection between Parsifal and the Ring and that is what sustains Paul Schofield’s thesis that Parsifal is the fifth opera of the Ring cycle, where the most important characters are redeemed: Wotan is reincarnated as Amfortas, Brünnhilde as Kundry, and Siegfried as Parsifal. Plácido Domingo summarizes well the quintessence of Parsifal with these words: “Through suffering, understanding. Through understanding, compassion. Through compassion, love” (Parsifal, documentary film directed by Tony Palmer, Kultur D1850, 90 minutes, 1998), a core idea that was unknown by National Socialism.

–

Wagner’s Parsifal (Studies in Musical Genesis, Structure, and Interpretation), by William Kinderman.

New York: Oxford University Press, 2013, x+ 327 pages. Hardcover.

Germán A. Bravo-Casas is a member of the Board of Directors of the Wagner Society of New York

Source: Wagner Opera

Leave a comment