Music: Richard Strauss

Libretto: Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Premiere: 25 January 1909, Königliches Opernhaus, Dresden

The courtyard of the Palace of Mycenae.

The servants wonder whether Elektra will be grieving over her father, as is her daily ritual. Daughter of King Agamemnon and Klytämnestra, Elektra appears and locks herself up in solitude straight away. The servants all criticize and mock her, except for one, who comes to her defense.

By herself, Elektra remembers how Agamemnon was assassinated upon his return from Troy, slain with an axe by Klytämnestra and her lover, Aegisth. Devastated with grief, Elektra is obsessed with the revenge she intends to take together with her sister, Chrysothemis, and her brother, Orest. The latter grew up far away from the palace, and Elektra keenly waits for him to return.

Opera, Blood, and Tears

celebrates the premiere of the opera

Elektra

January 25 at 10 pm EST

on Clubhouse

Chrysothemis interrupts Elektra, who is caught up in her thoughts, and warns her that Klytämnestra and Aegisth have decided to lock her up in a tower. Chrysothemis asks her sister to renounce vengeance and let life take over again. Elektra rejects the idea with disdain.

Klytämnestra arrives with her entourage. She has been preparing sacrifices, hoping to pacify the gods as she suffers from nightmares. She wants to talk to Elektra, and when her daughter’s words are more amenable than usual, Klytämnestra sends off her retinue and remains alone with the girl. Klytämnestra asks her daughter what remedy could restore her sleep, and Elektra reveals that a sacrifice may indeed free her from her nightmares. But when the queen, full of hope, asks who needs to be killed, Elektra replies that it is Klytämnestra herself who must die. Elektra goes on to describe with frenzied elation how her mother will succumb under Orest’s blows. Then the court is thrown into a panic: Two strangers have arrived and asked to be seen. The queen receives a message and leaves immediately without saying a single word to Elektra.

Chrysothemis frantically brings Elektra the terrible news: Orest is dead. At first, Elektra remains deaf to what has been said. Then, having lost all hope, she concludes that she and her sister must themselves take their vengeance without further delay. But Chrysothemis refuses to commit such a deed and flees. Elektra curses her, realizing that she will have to act alone.

One of the strangers, who claims to be a friend of Orest and has come to bear the news of his death, has now been at the court for a while. Elektra besieges him with questions. When she reveals her name, he is shaken. She doesn’t recognize him until the servants of the palace throw themselves at his feet: It is Orest who stands before her, Orest who tricked everyone into believing he was dead in order to sneak into the palace. Elektra is both elated and in despair—she feels immeasurable fondness for her brother and deep sadness about the life of a recluse she has chosen for herself. The two are interrupted by Orest’s guardian: The hour of vengeance has arrived, and the deed Orest has come to perform now needs to be done. Orest enters the palace. Elektra listens for the slightest noise. Klytämnestra is heard screaming as Orest slays her.

There is a moment of panic when the servants hear cries, but they flee when they learn that Aegisth is returning from the fields. As the sun is setting, he encounters Elektra, who, in a suddenly joyful mood, offers to light his way into the house. He discovers Klytämnestra’s body before Orest kills him as well.

Chrysothemis comes out of the palace and tells her sister about their brother’s return and the double murder of Klytämnestra and Aegisth. Elektra, hovering between ecstasy and madness, maintains that only silence and dance can celebrate their liberation. Beset by extreme frenzy, she dances until she drops: She will never be the one to have executed the act of revenge. Orest leaves the palace, alone and in silence.

Source: Metropolitan Opera

When Richard Strauss's Elektra was ushered on-stage in Dresden in January 1909, it was greeted by the critical equivalent of fits and screaming. Strauss, whose name was synonymous with "artistic scandal" on both sides of the Atlantic, was no stranger to controversy, but even so, many of the opera's original commentators were unusually vitriolic in their condemnation.

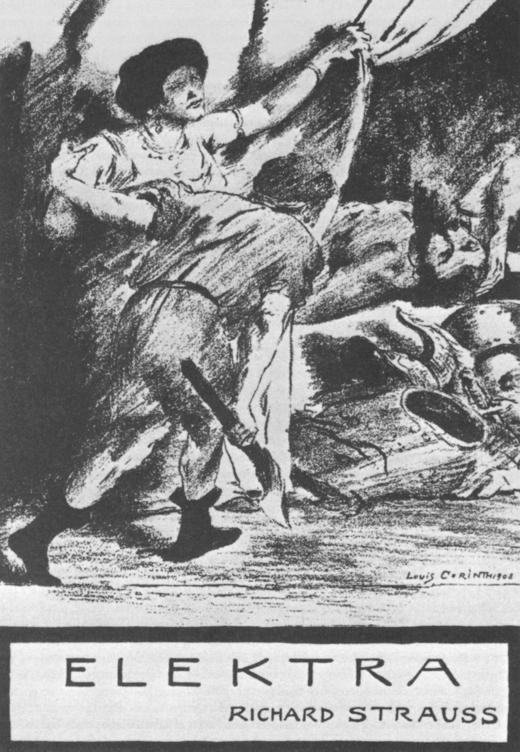

"The whole thing impresses one as a sexual aberration," one writer raged. "The blood mania appears as a terrible deformation of sexual perversity. This applies all the more because not only Elektra, but all the women are sexually tainted." One cartoonist went so far as to accuse Strauss and his librettist, the Austrian writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal, of the violation of classicism. Hofmannsthal - who had reworked his own "free adaptation" of Sophocles' Electra to form the libretto - was depicted holding the Greek dramatist down while Strauss battered him to death with a cymbal stick.

Yet beneath some of those early comments lurked distorted vestiges of the truth. The opera had hit raw nerves. Each age reinvents classical mythology in its own image. Strauss and Hofmannsthal were holding up a mirror to their times and many didn't like the reflection. A study of pathological hatred and self-perpetuating violence, Elektra forms a grim prophecy of the convulsions that dominated the 20th century and continue into the 21st.

The myth of Electra forms part of the vast classical saga of the house of Atreus, whose nominal founder, after a row with his brother, Thyestes, killed the latter's children and served them up to him to eat. Thereafter, the gods compelled various members of this tribe to take one life for another, then to be murdered in revenge in their turn.

The Atreidan myth is the only subject common to all three extant Greek tragic dramatists, though they approached it in different ways. Aeschylus's Oresteia focuses on chains of retribution and guilt. Euripides' Electra ironically questions belief in a metaphysical system that encourages crime only to punish it. Sophocles' Electra, centring on the heroine's grief for her father and her overwhelming desire for Orestes to return to shed his mother's blood, is widely regarded as the most psychologically advanced of Greek tragedies though Sophocles still presents the Atreides as motivated by divine commandments.

Hofmannsthal wrote his own Elektra in 1903 in response to a request for a version of Sophocles' from the Berlin-based director Max Reinhardt, and what he came up with was groundbreaking. Fastidious, intellectual and precociously erudite, Hofmannsthal's head was full of both the naturalistic theatre of Ibsen and Strindberg, and the murky psychological probings of symbolist poetry. His response to Reinhardt's request was to haul Sophocles into the present.

Much has been made of his ditching of many overt trappings of Greek drama, such as turning Sophocles' single-minded chorus into a gaggle of squabbling maids. Infinitely more important, however, was his decision to jettison the myth's metaphysics in their entirety. There is no divinely imposed pattern of retribution, no Furies to goad and torment his Orest, and the characters are consequently at the mercy of their own uncontrollable psyches and irrationalistic obsessions. Myth becomes the embodiment of psychological extremism as Hofmannsthal collides with his contemporary Freud.

Elektra has often been cited as the first play to take Freudian theory on board. In some respects this is erroneous, since the only psychoanalytic work Hofmannsthal knew at the time was Studies on Hysteria, co-written by Freud and Joseph Breuer and published in 1895. Elektra does, however, anticipate not only psychoanalysis, but other developments in psychiatry.

Hofmannsthal depicted Elektra as an obsessional neurotic long before Freud went public with his analysis of the condition. She and her mother are locked in a horrific co-dependency. Elektra's relentless thirst for blood fuels Klytemnestra's guilt, which she seeks in turn to assuage by turning to her daughter in the hope of some sort of solace. Terrified by nightmares of Orest's return, Klytemnestra asks Elektra to interpret and cure her dreams. In Hofmannsthal, however, unlike Freud, there are no cures: Elektra tells her mother her nightmares must continue until the axe falls and extinguishes her life.

Throughout, both sexual motivations and repression dominate. Elektra has sacrificed her sexuality to keep her obsession alive, and describes, in a scary passage, how she gave birth, parthenogenetically, to "curses and despair". Hofmannsthal, far from emphasising Freud, admitted that his principal influence was Hamlet. Both play and opera form an examination of the neurotic bifurcation between fantasy and action.

Nowadays, it is impossible to think of Hofmannsthal's text without Strauss's music, though the play proved influential in its own right, opening the way for later dramatists to reinvent classical myth as psychodrama. Jean Anouilh's Antigone and Sartre's The Flies are among its many successors. The playwright most strongly influenced by Hofmannsthal was Eugene O'Neill, who first read Elektra in the mid-1920s, and was inspired to write Mourning Becomes Electra as a result.

Strauss, meanwhile, saw Elektra during its opening run in the winter of 1903-04 and promptly contacted Hofmannsthal with a view to turning it into an opera. It wasn't until 1906 that they could actually start work together on Elektra, by which time, Strauss, to Hofmannsthal's alarm, began dithering. He wanted a libretto on a different subject, he told Hofmannsthal, who quietly held firm. Once work on the score was begun, Strauss, usually the most fluent and confident of musicians, began to suffer from composer's block.

Strauss was a secretive man, and his chirrupy letters to Hofmannsthal make no mention of the trauma he was going through, namely that the text was triggering deep anxieties deriving from his own ambivalent attitude towards his parents. Strauss's father, a domineering man, who encouraged his son's compositions but repeatedly disparaged the results, had died in 1905, an event which in turn caused Strauss's mother (whose mental health was never less than precarious) to have a massive breakdown, necessitating confinement in a sanatorium.

The subject matter of Elektra touched every raw nerve in Strauss's being and explains why he took so long over the score. Those same raw nerves, however, also spilled into every bar of the opera's music and also explain the torrential savagery of the emotions it recreates in the listener. Elektra is at once terrifying and elating, and to experience it is to go beyond the limits of reason into a world of naked, uncontrollable emotion. The collaboration between Strauss and Hofmannthal lasted for more than 20 years and became one of the most famous partnerships in operatic history, though neither was to produce work of such dreadful intensity again.

Source: the guardian

Leave a comment