Color is a matter of taste and of sensitivity.

Édouard Manet

Known as one of the most controversial artists in his time, Édouard Manet has risen above his detractors to prove his genuine talent that is worthy of emulation. With several paintings that have inspired young artists during that era, he revealed how innovation is not always welcomed by society, but it is one’s gateway to the future.

Édouard Manet was born on January 23, 1832, in the bustling city of Paris, to a well-off family. His parents were both highly recognized in their hometown, as his father was a reputable judge while his mother was of royal ancestry.

Early in his life, Manet knew that his ultimate desire was to become an artist, and he found support from his uncle to pursue this field. Along with his uncle, the two visited the Louvre where he found greater inspiration to improve on his artistic skills. In 1845, he decided to sign up for a drawing course, as he was encouraged by his uncle. It was during that time when he met a fellow art enthusiast, Antonin Proust, who soon became one of his dearest friends.

Although Manet developed a passion for the arts, his father had other plans for his future. In fact, he was forced to sail to Rio de Janeiro, so he could gain a membership to the Navy. However, he failed the examinations, much to his father’s disappointment. Yet, his failure also paved the way for his father to rethink his aspirations for the young Manet, and he soon gave in to his son’s ambition to become an artist. Hence, Manet was given that special opportunity to take up art education under the supervision of Thomas Couture. To further broaden his knowledge and artistic skills, Manet travelled to several parts of the world including Italy, the Netherlands and Germany. His adventures during his trips impacted his concept of various art forms and styles. In addition, he found inspiration from several artists including Titian, Caravaggio, Johannes Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Diego Velazquez.

Everything is mere appearance, the pleasures of a passing hour, a midsummer night’s dream. Only painting, the reflection of a reflection – but the reflection, too, of eternity – can record some of the glitter of this mirage.

Édouard Manet

With ample experience and confidence in himself, Manet decided to open his very first art studio. His early works were inspired by Gustave Courbet, who was a realist artist. Most of Manet’s artworks during the mid 1850s depicted contemporary themes and everyday life situations including bullfights, people in pavement cafes, singers, and Gypsies. His brush strokes were also rather loose, and the details were quite simplified and lacked much transitional tones.

However, he progressed from these themes and created artworks that were more of historical and religious nature. For instance, he painted various images of the suffering Christ, two of which were displayed in two prestigious art museums in the United States. Two of his other canvases also hung at the Salon, Paris, which was a major accomplishment among artists during this period.

One of his featured paintings there was an image of his parents, although this received little praises from art critics. His other work called The Spanish Singer gained better recognition from artists and art enthusiasts who frequented the Salon.

According to critics, Manet’s paintings had strange and less precise appearance, when compared side by side with other paintings featured at the Salon. His unique style caused intrigue, excitement and fascination among young artists who began to see art in a whole new light.

In Paris, one prestigious way for artists to introduce themselves to the public was by having their artworks displayed at the Salons. However, Manet came across numerous critics during the 1860s. When the Salon des Refuses was formed, in which paintings rejected by the jury of the Salon were exhibited, he decided to display his paintings that shocked several people. Primarily, it was the artist’s odd choice of subjects that bewildered critics such as the appearance of nude or barely-dressed women in his paintings. They were not impressed by Manet’s style, despite his originality and uniqueness. This led to attacks and negativity toward his works.

In 1864, Manet submitted more of his works to the Salon, yet these were all harshly criticized by fellow artists and intellectuals. His painting entitled Incident at a Bullfight was viewed by critics as a piece of artwork full of errors in terms of perspective while The Dead Christ and the Angels left others unimpressed due to lack of decorum. He was attacked for making Christ’s body resemble a dead coal miner’s body instead of someone ethereal and spiritual, which was what the actual Christ was like in their eyes. The lack of spirituality and realistic tones in the painting failed to meet the approval of most critics.

The same comments were cast upon his other artworks, particularly those that depicted modern scenes. Olympia, one of his most controversial paintings, disappointed most art critics not only because of the theme but Manet’s way of presenting the subject. The image of a nude woman in that painting did not seem acceptable or decent enough. While “Olympia” was the subject of caricatures in the popular press, it was championed by the French avant-garde community, and the painting’s significance was appreciated by artists such as Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and later Gauguin, and Van Gogh.

Manet’s paintings were influenced by the Impressionist, yet he was uninterested in becoming involved with exhibitions during this era in art. He was more keen on displaying his works at the Salon, so he could avoid any notions that he was a representative of the impressionist style of painting. Although Manet was also fond of using lighter colors, his paintings often had a hint of black, which was not typical in most paintings during his time.

His last work was called A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, which was displayed at the Salon, in 1882. Prior to that year, he received a special award from the French Government, which was the Légion d’honneur. It was one of the highest form of recognition that he has received throughout his life.

Since 1880, Manet suffered from serious medical conditions, which was also one of the reasons why he was forced to receive treatment at Bellevue. Thus, he decided to rent a villa in the quieter side of Paris’ suburbs. It was in this location where he painted a portrait of his wife, Suzanne Leenhoff, the last of the numerous portraits of his wife that he completed. He remained passionate about art even until his untimely death, in 1883. Besides 420 paintings, Manet left behind a reputation that would forever define him as the first of the moderns, and a bold, influential artist.

Source: Manet

Dead Toreador, 1864 originally formed part of a much larger one, Incident in the Bull Ring, which was exhibited at the 1864 Salon. Manet, dissatisfied with it, cut it in two. One half, Bullfight, is in the Frick Collection in New York, and the other is this Dead Toreador, which was the lower part of the original work. (Manet is known to have cut up several of his pictures in this way.)

This is one of Manet's most sensitive and delicate works. Although the body is perhaps a little wooden, or at any rate exaggeratedly stiff, the color harmonies reveal Manet as a master colorist. What words can describe the old-rose of the muleta, the silvery, silken texture of the white stockings and sash, and the deep, resonant blacks against the dark olive background.

Along with the Dejeuner sur I'herbe and Olympia, The Surprised Nymph is one of Manet's major treatments of the quintessential subject-matter of academic practice: the female nude. Like the two slightly later paintings, this is a large work and one which clearly took Manet some time to produce.

It is believed that the model for the painting was Suzanne Leenhoff, Manet's future wife. In part, the work may be a pun on her name, for her pose is reminiscent of that of conventional depictions of Susannah disturbed by the elders, at once provocative and chaste. Around the time he produced this work, Manet moved into a new apartment on the rue de l'Hotel de Ville with Suzanne and Leon and the ambivalent attitude of the nude woman may suggest the artist's response to his future wife who in later paintings is shown as an upright member of the bourgeoisie. She is perhaps best understood in contrast to the nude woman in the Dejeuner for whom she represents both a prototype and a transformation. Whereas The Surprised Nymph depicts a naked bourgeois woman who shields her body from the gaze of the voyeuristic onlooker, she is presented in the Dejeuner as a professional working model apparently flaunts her body and subverts the traditional roles of the spectator and the nude.

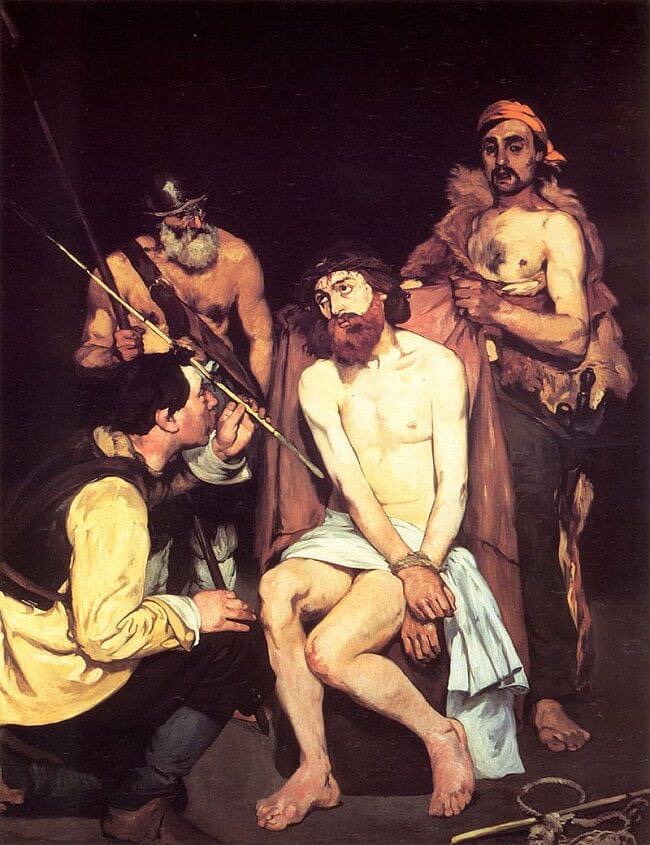

Although the art of Eduoard Manet was often rooted in references to the history of art, his subjects - parks, cafes, racetracks - were usually quite modern. Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers represents a foray into religious imagery that was rare for Manet (and for his peers in the French avant-garde). Its theme, heroic scale, and dark colors related it to Old Master paintings. Its treatment, however, reflects Manet's usual daring, his flouting of convention. Here, the viewer is confronted with a very human, vulnerable Jesus whose fate is no longer his to determine.

Manet depicted the moment when Jesus' captors have mocked the "king of the Jews" by crowning him with thorns and covering him with a purple robe. Although this taunting is followed by beatings, according to Gospel narrative, Manet's three earthy and contemporary-looking soldiers appear ambivalent as they surround the pale, stark figure of Jesus. One gazes at him, one kneels in apparent homage, and one holds the purple cloak in such a way as to suggest that he wishes to cover Christ's nakedness, rather than strip him. Manet's use of stark contrasts, flat forms, and a dark palette of t hickly applied pigment enhances this raw and powerful impression.

Source: Manet

Leave a comment