Gulistān, KSS 63

Piece details

Written for: Piano

Date composed: 1940

Dedicatee: Harold Morland

Approximate duration (minutes): 35

Manuscript pages: 28

Manuscript location: Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel

Sorabji wrote a number of nocturnes, from the earliest stages in his development until his final years. These include some of his better-known works such as Le jardin parfumé and Djâmi. Several works — such as In the Hothouse of 1918 and the much later Villa Tasca, written 1979–80 — are not designated as nocturnes, but nonetheless occupy the same languorous, exotic atmosphere that characterises Gulistān, arguably his most successful essay in the genre. The poet Sa‘dī of Shīrāz (ca. 1213–92) finished the extended Gulistān in 1258, after many years of travelling. Although Sorabji’s nocturne is not a programmatic work, that the poem had significant influence on the work’s composition is undeniable. This suggestion is strengthened by the fact Sorabji prefaced his score of Gulistān with two texts. The first is an extract from Sa‘di’s poem Fidelity, here translated by Charles Hopkins:

“For some years I had travelled with a particular friend, and on many occasions we had shared bread and salt together. I say this to demonstrate the total intimacy of our friendship. One day, however, wishing to get the better of me, he allowed himself to cause me distress, and we became less close. Despite this painful episode we still remained friendly, and I later learnt that he had, in company, recited this qaṣīdah of my composition:

“When my friend, smiling, crossed the threshold of my home he sprinkles salt on the open wound of my love. What should happen if a lock of his hair were to brush my forehead like the alms of a rich man dropping into the palm of one less fortunate?”

Several of those present applauded the sentiment of this verse, and my old companion was especially effusive in his praise. He had been deeply saddened at losing my affection, and unhesitatingly accepted that he had been to blame … I realised that he was eager for a reconciliation and addressed the poem which follows to him as a mark of my forgiveness:

“We were once true to one another. It was you who were unjust. I could not have foreseen that you would distance yourself from me, since I had given my heart to you … even though there were a good many others to whom I was close! Come back, and you will be loved again as never before!”

The second text, actually designated as a preface by Sorabji, is taken from Norman Douglas’ South Wind:

“What, sir, would you call the phenomenon of today? What is the outstanding feature of modern life? The bankruptcy, the proven fatuity, of everything that is bound up under the name of Western civilization. Men are perceiving, I think, the baseness of mercantile and military ideals, the loftiness of those older ones. They will band together, the elect of every nation, in god-favoured regions around the Inland Sea, there to lead serener lives. To those who have hitherto preached indecorous maxims of conduct they will say: What is all this ferocious nonsense about strenuousness? An unbecoming fluster. And who are you, to dictate how we shall order our day? Go! Shiver and struggle in your hyperborean dens. Trample about those misty rain-sodden fields, and hack each other’s eyes out with antediluvian bayonets. Or career up and down the ocean, in your absurd ships, to pick the pockets of men better than yourselves. This is your mode of self-expression. It is not ours.”

(notes: Jonathan Powell)

Source: The Sorabji Archive

Gulistān (Golestan) literally ’The Flower Garden’, is a landmark of Persian literature, perhaps its single most influential work of prose, written in 1258 CE, it is one of two major works of the Persian poet Sa’di, considered one of the greatest medieval Persian poets. It is also one of his most popular books, and has proved deeply influential in the West as well as the East. The Golestan is a collection of poems and stories, just as a flower-garden is a collection of flowers. It is widely quoted as a source of wisdom. The well-known aphorism still frequently repeated in the western world, about being sad because one has no shoes until one meets the man who has no feet “whereupon I thanked Providence for its bounty to myself” is from the Golestan.

The minimalist plots of the Golestan’s stories are expressed with precise language and psychological insight, creating a “poetry of ideas” with the concision of mathematical formulas. The book explores virtually every major issue faced by humankind with both an optimistic and a subtly satirical tone.[4] There is much advice for rulers. But “each word of Sa’di has seventy-two meanings”, and the stories, alongside their entertainment value and practical and moral dimension, frequently focus on the conduct of dervishes and are said to contain Sufi teachings.

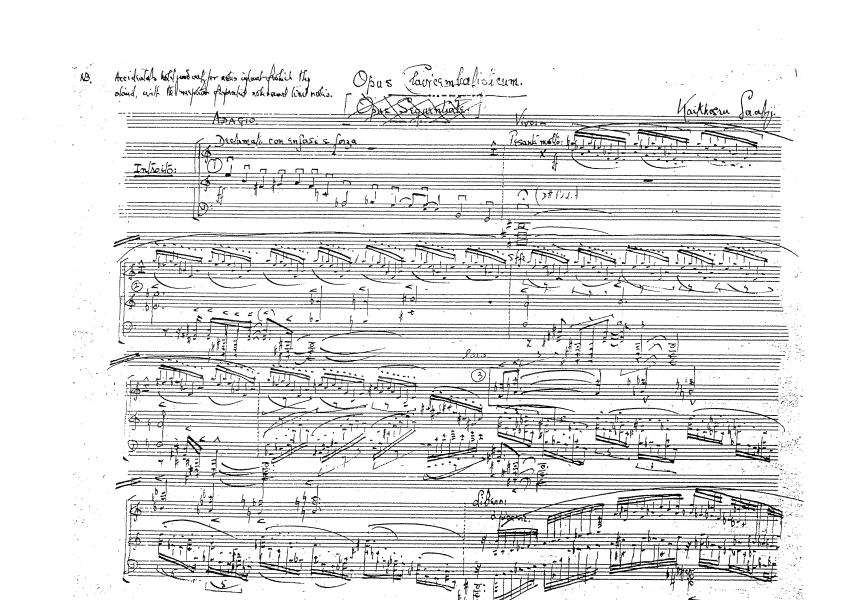

Opus Clavicembalisticum MCMXXX (1930)

Piece details:

Written for: Piano

Date composed: 1929–30

Dedicatee: Hugh M’Diarmid

Approximate duration (minutes): 285

Manuscript pages: 260

Manuscript location: J.W.Jagger Library, University of Cape Town

Structure:

I PARS PRIMA

i. Introito

ii. Preludio-Corale

iii. Fuga I

iv. Fantasia

v. Fuga II

II PARS ALTERA

vi. Interludium primum

vii. Cadenza I

viii. Fuga III

III PARS TERTIA

ix. Interludium: Toccata-Adagio-Passacaglia

x. Cadenza II

xi. Fuga IV

xii. Coda-Stretta

Sorabji’s Opus clavicembalisticum is stuff of legend, more talked and written about than heard, music of proportions and hue so ‘other’. It’s a coming-of-age work, a masterpiece in the Renaissance sense of the word: one where an artist creates for the first time – not without risk – a bold statement and something truly in their own image. With its Baroque structures it is at once Bachian but its sound reaches far into the future; like several of Sorabji’s pieces, its duration extends far outside the norms of Western concert music. While the myth of unplayability associated with Sorabji’s music has long been dispelled, the aura of transcendental concentration for both performer and audience still surrounds presentations of his work.

For the form and to a certain extent the style of Opus clavicembalisticum, Sorabji took as a starting point Busoni’s Fantasia contrappuntistica (which itself had started life as a completion of the final contrapunctus of Bach’s The Art of Fugue); the result is clearly intended as a homage to the Italian composer-pianist. Sorabji idolised Busoni whom he had heard in concert in the early 1920s and also met in person.

A disastrous performance in 1936 of part of his Opus clavicembalisticum led Sorabji to strongly discourage any further public airings of his music, explaining that ‘no performance at all’ is vastly preferable to ‘an obscene travesty’; while such a protective instinct is understandable in principle, Sorabji is perhaps the only composer of note ever to have given expression to it and then attempted to see it through in practice. He was well aware that ‘performers with the sheer grit, determination and staying power ever to attempt his very forbidding scores’ would be such ‘raræ aves that they may be relied on to deduce, from internal evidence, what sort of treatment the music calls for’. The notes to be mastered, for him, were ‘a pretty effective barrier to the typical artistic incompetence of the many-too-many of the virtuoso tribe’. However, in 1976 Sorabji finally relented in favour of the pianist Yonty Solomon, whom he had heard in BBC broadcasts that impressed him greatly. Solomon’s subsequent performances of several of Sorabji’s works led to increasing international interest: many more performers began to produce performances, broadcasts and commercial recordings bringing the music an ever-widening group of admirers.

Having recently attended three recitals by Egon Petri and two performances of Busoni’s Fantasia contrappuntistica, one by Petri and one by another of Busoni’s pupils, Eduard Steuermann (1892–1964), Sorabji wrote of the “rather terrifying quality of the work, its monumental grandeur, its severe and ascetic splendour, its eerie magnificence, its utter uniqueness”, adding that it was “a terrible as well as a mighty work, for, like the Hammerklavier, it will turn and rend any rash weakling who dares to try to invoke it”. Busoni’s work and its performance were for him a religious, even mystical, experience—and this was to be true of Opus clavicembalisticum. Upon reaching the end of the second variation of “Interludium primum”, he decided to change the work’s title from Opus sequentiale to Opus clavicembalisticum. Sorabji expected to complete “the sternest, most uncompromising work I have ever done, austere, ascetic”. Sorabji explained to his friend the composer Erik Chisholm the meaning of the Latin title: “Opus = a work: Clavicembalum = a cymbalon with keys: plus termination = isticum= adjectival indicating belonging to or pertaining to.” On 25 June he could at last announce that he had completed the composition.

‘With a racking head and literally my whole body shaking as with ague (agyooo) I write this and tell you that I have just this early afternoon finished Clavicembalisticum (252 pages …) […] The closing 4 pages are as cataclysmic and catastrophic as anything I’ve ever done—the harmony bites like nitric acid, the counterpoint grinds like the mills of God to close finally on this implacable monosyllable: [musical example representing the work’s final G sharp minor chord in the left hand with a quasi-cluster chord (B–D–F–G–A–B) in the right hand] “I am the Spirit that denies!”’ [Letter to Erik Chisholm]

Here Sorabji refers to the final dissonant chord, which defeats the listener’s expectation of a powerful and rich consonant sonority (most probably that of C sharp major, given its importance elsewhere in the work), and refers to the words spoken by Mephistopheles shortly after his entrance in the first Studierzimmer scene in Goethe’s Faust (line 1338: “Ich bin der Geist, der stets verneint!”). I am the spirit who stands in denial.

Opus clavicembalisticum comprises three parts consisting of five, three, and four movements, respectively. The movements are ordered so that each part contains a balance of fugues, virtuoso sections in toccata style, and variations. The very short Introito opens with a starkly declaimed motto of fourteen notes leading to a low

D sharp, which becomes the top note of a D sharp minor chord in first inversion; both the motto and the chord are used several times as a unifying device. The motto contains ten of the twelve chromatic pitches except C sharp (a most important structural axis in the work) and D. The “Introito” also states two further chorale-like motives, which are closely related to the theme of the “Preludio corale” from Busoni’s Fantasia contrappuntistica.

The Preludio-corale that follows, an even clearer link to the initial section of Busoni’s masterpiece, opens with a modified statement of the motto. It works out the thematic ideas heard previously and anticipates the incipit of “Fuga I” twice. Fuga I, in a moderate tempo, uses a very short subject in slow values against two counter subjects. This subject is quite similar in outline to “Contrapunctus XV” from Bach’s Art of Fugue, also found in Busoni’s Fantasia contrappuntistica as the subject of the first fugue. A virtuoso Fantasia provides relief from the contrapuntal texture. This toccata-like section states quite prominently the opening motto of “Fuga I”. The first subject of the Fuga II is a long animated theme in quavers, with only two instances of semiquavers as ornamentation; the second one is more varied rhythmically. Yet the result is essentially a massive movement in even rhythmic values.

The theme of the Interludium primum consists of two almost similar strains in slow and long note values in the medium register above a series of rich chords in crotchets, each ending on a noble C sharp major chord, a sonority that will become prominent later. Cadenza I, a furious toccata, begins with a semiquaver run notated on a single line. The first page recalls the second countersubject of “Fuga I”. The music grows until a brief fanfare-like, pompous, and heavy bitonal chordal passage, after which the toccata style resumes. In its sharp version, this note refers to the opening chord of both the “Introito” and the “Interludium alterum”. Fuga tertia triplex, which at more than thirty minutes is longer than the previous two, features long, sinuous subjects consisting mostly of crotchets and quavers. It concludes very slowly and massively on a C sharp major sonority (with added notes). The tripartite Interludium alterum is the most massive movement of the work. It lasts about an hour and requires herculean stamina. The introductory “Toccata” begins with the D sharp minor sonority heard at the very opening, above which is heard a variant of the motto. Like the previous two virtuoso sections, it relies mostly on capricious runs of semiquavers. The “Adagio” is the work’s only section in nocturne style and the only complete one in a slow tempo. The final gesture, indeed, is a descending series of chords played “Adagissimo” above a C sharp major chord in the low register; it concludes on an even richer version of the same chord, sounded ff. The eighty-one variations of the “Passacaglia” are based on an ostinato that has much in common with the third subject of “Fuga IV”.

Some sections may be singled out. Var. 53, marked “Quasi tambura”, consists of a highly ornamented, Oriental-sounding, melody pitted against an F sharp ostinato played in semiquavers over the keyboard’s entire range; the pedal point, reduced to F sharp continues into var. 54. The last two variations, spread on four staves, state the theme in chords; whatever free space remains between the thematic notes is filled with frightening runs consisting of alternating dyads and triads; the final variation amplifies the climax even more by filling the space between the notes with the chordal equivalent of blind octaves. It is doubtful that anyone, including Sorabji, has ever written a more powerful passage for two hands. As one may expect, this gigantic peal of bells ends on a C sharp major chord; it is followed by a short “Epilogo” consisting of a final statement of the theme.

Cadenza II requires that the pianist still have stamina to spare to attack an expansive toccata, marked “Vivo”. Fuga IV quadruplex offers more variety in its choice of subjects than the previous fugues. Whereas the first one is the usual mixture of quavers, crotchets, and minims, the second one is a very swiftly moving line of twenty-eight beats, mostly in semiquavers. For the third subject, Sorabji returns to a severe style, mostly in long note values. The final subject, again very long (twenty-seven beats), is a most capricious line exhibiting considerable rhythmic variety. The fourth fugue ends with three strettos (“Le strette”), in which the final subject is presented five times in very close succession. The Coda-Stretta is marked “Quasi organo piano”. At one point, after a final statement of the opening motto and amid the gigantic peal of chords into which he has transformed the second subject of “Fuga IV”, Sorabji recalls the theme of “Fuga I” before reaching a powerful D flat = (= C sharp) sonority, which provides the basis for a blazing run covering the entire keyboard. This opens the way to a final contrapuntal section involving the first subjects of the first three fugues. A final surge of radiant sonorities is reached when a glorious C sharp major chord marks the end of the stretto and the beginning of the concluding “Più largo”. From the active chordal figurations in rapid note values emerges a magnificent sequence of chords, the top notes of which match those of the subject of “Fuga I”, thus rounding out the entire structure with a forceful reminder of how this huge complex of ten fugues began. The final G sharp minor chord, a link with the end of “Fuga I”, is sounded again in the low register with a major ninth chord on G in first inversion above it. As mentioned earlier, Sorabji almost sadistically defeats the listener’s expectation of a C sharp major sonority, so often heard at important structural points, and prefers to be the “spirit that denies”. Seen in the perspective of his entire output, Opus clavicembalisticum is only one of many peaks, because Sorabji, between 1931 and 1964, would write eight works for solo piano of approximately the same length or even longer. It is one of the longest, most ambitious works ever written for any solo instrument only when one does not know what was to follow.

© Marc-André Roberge, from his Opus Sorabjianum

About the music itself – the extravagantly opulent, exoticism and intellectuality of his monumental compositions bring together with dazzling virtuosity the ineffable flow between the East and West, striking some primordial chord in the engulfed and mesmerised listener.

Sorabji’s roots perhaps are in the exploratory styles of Busoni, Szymanowski, Scriabin and even to a certain extent Rachmaninoff. All of these composers are supremely pianistic figures dominating our perceptions of post-Romantic musical genres; they all possessed idiosyncratically original insights into a monumental utilisation of the piano in orchestral terms. But with Kaikhosru Sorabji a unique contributory factor is the explosive fusion of his Parsi origins with the debonair sophistication of the world of the Sitwells and other contemporaneous intellectuals who created their own artistic milieu with such defined personality traits. The profusion of eastern raga-like improvisations, melismatic chanting, modal tonalities and atonalities, are an inherent part of Sorabji’s creative genius. The mammoth piano technique inherent in his works is kaleidoscopically diverse and a virtuosic approach is as necessary as a profoundly sensitive ear for a wide spectrum of sonorities from utmost delicacy to volcanic ferocity.

Leave a comment