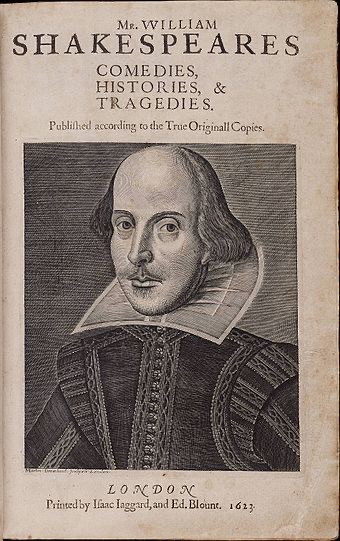

William Shakespeare, baptized April 26, 1564, born in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England, is the poet, dramatist, and actor often called the English national poet. He is considered by many to be the greatest dramatist of all time.

Shakespeare occupies a position unique in world literature. Other poets, such as Homer and Dante, and novelists, such as Leo Tolstoy and Charles Dickens, have transcended national barriers, but no writer’s living reputation can compare to that of Shakespeare, whose plays, written in the late 16th and early 17th centuries for a small repertory theatre, are now performed and read more often and in more countries than ever before. The prophecy of his great contemporary, the poet and dramatist Ben Jonson, that Shakespeare “was not of an age, but for all time,” has been fulfilled.

Opera, Blood, and Tears

presents

The Tempest by Thomas Adès

in celebration of the life for literature of

William Shakespeare

April 26 at 5 pm EST

on Clubhouse

It may be audacious even to attempt a definition of his greatness, but it is not so difficult to describe the gifts that enabled him to create imaginative visions of pathos and mirth that, whether read or witnessed in the theatre, fill the mind and linger there. He is a writer of great intellectual rapidity, perceptiveness, and poetic power. Other writers have had these qualities, but with Shakespeare the keenness of mind was applied not to abstruse or remote subjects but to human beings and their complete range of emotions and conflicts. Other writers have applied their keenness of mind in this way, but Shakespeare is astonishingly clever with words and images, so that his mental energy, when applied to intelligible human situations, finds full and memorable expression, convincing and imaginatively stimulating. As if this were not enough, the art form into which his creative energies went was not remote and bookish but involved the vivid stage impersonation of human beings, commanding sympathy and inviting vicarious participation. Thus, Shakespeare’s merits can survive translation into other languages and into cultures remote from that of Elizabethan England.

Life

Although the amount of factual knowledge available about Shakespeare is surprisingly large for one of his station in life, many find it a little disappointing, for it is mostly gleaned from documents of an official character. Dates of baptisms, marriages, deaths, and burials; wills, conveyances, legal processes, and payments by the court—these are the dusty details. There are, however, many contemporary allusions to him as a writer, and these add a reasonable amount of flesh and blood to the biographical skeleton.

The parish register of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, shows that he was baptized there on April 26, 1564; his birthday is traditionally celebrated on April 23. His father, John Shakespeare, was a burgess of the borough, who in 1565 was chosen an alderman and in 1568 bailiff (the position corresponding to mayor, before the grant of a further charter to Stratford in 1664). He was engaged in various kinds of trade and appears to have suffered some fluctuations in prosperity. His wife, Mary Arden, of Wilmcote, Warwickshire, came from an ancient family and was the heiress to some land. (Given the somewhat rigid social distinctions of the 16th century, this marriage must have been a step up the social scale for John Shakespeare.)

Stratford enjoyed a grammar school of good quality, and the education there was free, the schoolmaster’s salary being paid by the borough. No lists of the pupils who were at the school in the 16th century have survived, but it would be absurd to suppose the bailiff of the town did not send his son there. The boy’s education would consist mostly of Latin studies—learning to read, write, and speak the language fairly well and studying some of the Classical historians, moralists, and poets. Shakespeare did not go on to the university, and indeed it is unlikely that the scholarly round of logic, rhetoric, and other studies then followed there would have interested him.

Instead, at age 18 he married. Where and exactly when are not known, but the episcopal registry at Worcester preserves a bond dated November 28, 1582, and executed by two yeomen of Stratford, named Sandells and Richardson, as a security to the bishop for the issue of a license for the marriage of William Shakespeare and “Anne Hathaway of Stratford,” upon the consent of her friends and upon once asking of the banns. (Anne died in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare. There is good evidence to associate her with a family of Hathaways who inhabited a beautiful farmhouse, now much visited, 2 miles [3.2 km] from Stratford.) The next date of interest is found in the records of the Stratford church, where a daughter, named Susanna, born to William Shakespeare, was baptized on May 26, 1583. On February 2, 1585, twins were baptized, Hamnet and Judith. (Hamnet, Shakespeare’s only son, died 11 years later.)

How Shakespeare spent the next eight years or so, until his name begins to appear in London theatre records, is not known. There are stories—given currency long after his death—of stealing deer and getting into trouble with a local magnate, Sir Thomas Lucy of Charlecote, near Stratford; of earning his living as a schoolmaster in the country; of going to London and gaining entry to the world of theatre by minding the horses of theatregoers. It has also been conjectured that Shakespeare spent some time as a member of a great household and that he was a soldier, perhaps in the Low Countries. In lieu of external evidence, such extrapolations about Shakespeare’s life have often been made from the internal “evidence” of his writings. But this method is unsatisfactory: one cannot conclude, for example, from his allusions to the law that Shakespeare was a lawyer, for he was clearly a writer who without difficulty could get whatever knowledge he needed for the composition of his plays.

Career in the theatre

The first reference to Shakespeare in the literary world of London comes in 1592, when a fellow dramatist, Robert Greene, declared in a pamphlet written on his deathbed:

"There is an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers heart wrapt in a Players hide supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you; and, being an absolute Johannes Factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country."

What these words mean is difficult to determine, but clearly they are insulting, and clearly Shakespeare is the object of the sarcasms. When the book in which they appear (Greenes, groats-worth of witte, bought with a million of Repentance, 1592) was published after Greene’s death, a mutual acquaintance wrote a preface offering an apology to Shakespeare and testifying to his worth. This preface also indicates that Shakespeare was by then making important friends. For, although the puritanical city of London was generally hostile to the theatre, many of the nobility were good patrons of the drama and friends of the actors. Shakespeare seems to have attracted the attention of the young Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd earl of Southampton, and to this nobleman were dedicated his first published poems, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece.

One striking piece of evidence that Shakespeare began to prosper early and tried to retrieve the family’s fortunes and establish its gentility is the fact that a coat of arms was granted to John Shakespeare in 1596. Rough drafts of this grant have been preserved in the College of Arms, London, though the final document, which must have been handed to the Shakespeares, has not survived. Almost certainly William himself took the initiative and paid the fees. The coat of arms appears on Shakespeare’s monument (constructed before 1623) in the Stratford church. Equally interesting as evidence of Shakespeare’s worldly success was his purchase in 1597 of New Place, a large house in Stratford, which he as a boy must have passed every day in walking to school.

How his career in the theatre began is unclear, but from roughly 1594 onward he was an important member of the Lord Chamberlain’s company of players (called the King’s Men after the accession of James I in 1603). They had the best actor, Richard Burbage; they had the best theatre, the Globe (finished by the autumn of 1599); they had the best dramatist, Shakespeare. It is no wonder that the company prospered. Shakespeare became a full-time professional man of his own theatre, sharing in a cooperative enterprise and intimately concerned with the financial success of the plays he wrote.

Unfortunately, written records give little indication of the way in which Shakespeare’s professional life molded his marvelous artistry. All that can be deduced is that for 20 years Shakespeare devoted himself assiduously to his art, writing more than a million words of poetic drama of the highest quality.

Private life

...

Shakespeare’s will (made on March 25, 1616) is a long and detailed document. It entailed his quite ample property on the male heirs of his elder daughter, Susanna. (Both his daughters were then married, one to the aforementioned Thomas Quiney and the other to John Hall, a respected physician of Stratford.) As an afterthought, he bequeathed his “second-best bed” to his wife; no one can be certain what this notorious legacy means. The testator’s signatures to the will are apparently in a shaky hand. Perhaps Shakespeare was already ill. He died on April 23, 1616. No name was inscribed on his gravestone in the chancel of the parish church of Stratford-upon-Avon. Instead these lines, possibly his own, appeared:

Good friend, for Jesus’ sake forbear

To dig the dust enclosed here.

Blest be the man that spares these stones,

And curst be he that moves my bones.

John Russell Brown

Terence John Bew Spencer

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Sexuality of William Shakespeare

Like so many circumstances of Shakespeare’s personal life, the question of his sexual nature is shrouded in uncertainty. At age 18, in 1582, he married Anne Hathaway, a woman who was eight years older than he. Their first child, Susanna, was born on May 26, 1583, about six months after the marriage ceremony. A license had been issued for the marriage on November 27, 1582, with only one reading (instead of the usual three) of the banns, or announcement of the intent to marry in order to give any party the opportunity to raise any potential legal objections. This procedure and the swift arrival of the couple’s first child suggest that the pregnancy was unplanned, as it was certainly premarital. The marriage thus appears to have been a “shotgun” wedding. Anne gave birth some 21 months after the arrival of Susanna to twins, named Hamnet and Judith, who were christened on February 2, 1585. Thereafter William and Anne had no more children. They remained married until his death in 1616.

Were they compatible, or did William prefer to live apart from Anne for most of this time? When he moved to London at some point between 1585 and 1592, he did not take his family with him. Divorce was nearly impossible in this era. Were there medical or other reasons for the absence of any more children? Was he present in Stratford when Hamnet, his only son, died in 1596 at age 11? He bought a fine house for his family in Stratford and acquired real estate in the vicinity. He was eventually buried in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford, where Anne joined him in 1623. He seems to have retired to Stratford from London about 1612. He had lived apart from his wife and children, except presumably for occasional visits in the course of a very busy professional life, for at least two decades. His bequeathing in his last will and testament of his “second best bed” to Anne, with no further mention of her name in that document, has suggested to many scholars that the marriage was a disappointment necessitated by an unplanned pregnancy.

What was Shakespeare’s love life like during those decades in London, apart from his family? Knowledge on this subject is uncertain at best. According to an entry dated March 13, 1602, in the commonplace book of a law student named John Manningham, Shakespeare had a brief affair after he happened to overhear a female citizen at a performance of Richard III making an assignation with Richard Burbage, the leading actor of the acting company to which Shakespeare also belonged. Taking advantage of having overheard their conversation, Shakespeare allegedly hastened to the place where the assignation had been arranged, was “entertained” by the woman, and was “at his game” when Burbage showed up. When a message was brought that “Richard the Third” had arrived, Shakespeare is supposed to have “caused return to be made that William the Conqueror was before Richard the Third. Shakespeare’s name William.” This diary entry of Manningham’s must be regarded with much skepticism, since it is verified by no other evidence and since it may simply speak to the timeless truth that actors are regarded as free spirits and bohemians. Indeed, the story was so amusing that it was retold, embellished, and printed in Thomas Likes’s A General View of the Stage (1759) well before Manningham’s diary was discovered. It does at least suggest, at any rate, that Manningham imagined it to be true that Shakespeare was heterosexual and not averse to an occasional infidelity to his marriage vows. The film Shakespeare in Love (1998) plays amusedly with this idea in its purely fictional presentation of Shakespeare’s torchy affair with a young woman named Viola De Lesseps, who was eager to become a player in a professional acting company and who inspired Shakespeare in his writing of Romeo and Juliet—indeed, giving him some of his best lines.

Apart from these intriguing circumstances, little evidence survives other than the poems and plays that Shakespeare wrote. Can anything be learned from them? The sonnets, written perhaps over an extended period from the early 1590s into the 1600s, chronicle a deeply loving relationship between the speaker of the sonnets and a well-born young man. At times the poet-speaker is greatly sustained and comforted by a love that seems reciprocal. More often, the relationship is one that is troubled by painful absences, by jealousies, by the poet’s perception that other writers are winning the young man’s affection, and finally by the deep unhappiness of an outright desertion in which the young man takes away from the poet-speaker the dark-haired beauty whose sexual favours the poet-speaker has enjoyed (though not without some revulsion at his own unbridled lust, as in Sonnet 129). This narrative would seem to posit heterosexual desire in the poet-speaker, even if of a troubled and guilty sort; but do the earlier sonnets suggest also a desire for the young man? The relationship is portrayed as indeed deeply emotional and dependent; the poet-speaker cannot live without his friend and that friend’s returning the love that the poet-speaker so ardently feels. Yet readers today cannot easily tell whether that love is aimed at physical completion. Indeed, Sonnet 20 seems to deny that possibility by insisting that Nature’s having equipped the friend with “one thing to my purpose nothing”—that is, a penis—means that physical sex must be regarded as solely in the province of the friend’s relationship with women: “But since she [Nature] pricked thee out for women’s pleasure, / Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.” The bawdy pun on “pricked” underscores the sexual meaning of the sonnet’s concluding couplet. Critic Joseph Pequigney has argued at length that the sonnets nonetheless do commemorate a consummated physical relationship between the poet-speaker and the friend, but most commentators have backed away from such a bold assertion.

Irish author Oscar Wilde, photograph (albumen silver print)by Napoleon Sarony, 1882.

Britannica Quiz

English and Irish Playwrights (Part One) Quiz

A significant difficulty is that one cannot be sure that the sonnets are autobiographical. Shakespeare is such a masterful dramatist that one can easily imagine him creating such an intriguing story line as the basis for his sonnet sequence. Then, too, are the sonnets printed in the order that Shakespeare would have intended? He seems not to have been involved in their publication in 1609, long after most of them had been written. Even so, one can perhaps ask why such a story would have appealed to Shakespeare. Is there a level at which fantasy and dreamwork may be involved?

The plays and other poems lend themselves uncertainly to such speculation. Loving relationships between two men are sometimes portrayed as extraordinarily deep. Antonio in Twelfth Night protests to Sebastian that he needs to accompany Sebastian on his adventures even at great personal risk: “If you will not murder me for my love, let me be your servant” (Act II, scene 1, lines 33–34). That is to say, I will die if you leave me behind. Another Antonio, in The Merchant of Venice, risks his life for his loving friend Bassanio. Actors in today’s theatre regularly portray these relationships as homosexual, and indeed actors are often incredulous toward anyone who doubts that to be the case. In Troilus and Cressida, Patroclus is rumoured to be Achilles’ “masculine whore” (V, 1, line 17), as is suggested in Homer, and certainly the two are very close in friendship, though Patroclus does admonish Achilles to engage in battle by saying,

A woman impudent and mannish grown

Is not more loathed than an effeminate man

In time of action

(III, 3, 218–220)

Again, on the modern stage this relationship is often portrayed as obviously, even flagrantly, sexual; but whether Shakespeare saw it as such, or the play valorizes homosexuality or bisexuality, is another matter.

Certainly his plays contain many warmly positive depictions of heterosexuality, in the loves of Romeo and Juliet, Orlando and Rosalind, and Henry V and Katharine of France, among many others. At the same time, Shakespeare is astute in his representations of sexual ambiguity. Viola—in disguise as a young man, Cesario, in Twelfth Night—wins the love of Duke Orsino in such a delicate way that what appears to be the love between two men morphs into the heterosexual mating of Orsino and Viola. The ambiguity is reinforced by the audience’s knowledge that in Shakespeare’s theatre Viola/Cesario was portrayed by a boy actor of perhaps 16. All the cross-dressing situations in the comedies, involving Portia in The Merchant of Venice, Rosalind/Ganymede in As You Like It, Imogen in Cymbeline, and many others, playfully explore the uncertain boundaries between the genders. Rosalind’s male disguise name in As You Like It, Ganymede, is that of the cupbearer to Zeus with whom the god was enamoured; the ancient legends assume that Ganymede was Zeus’s catamite. Shakespeare is characteristically delicate on that score, but he does seem to delight in the frisson of sexual suggestion.

Source: Britannica

The Tempest

Opera in three acts

Composer: Thomas Adès

Libretto: Meredith Oakes

Based on the play The Tempest, by William Shakespeare.

Premiere: Royal Opera House, London, February 10 2004

ACT I

Miranda suspects that the magic practices of her father, Prospero, are responsible for a huge storm that has sunk a passing ship. Prospero informs her that the people on board were the court of Naples. They are his enemies, whom he has shipwrecked in order to punish. He recounts the story of being usurped and conjures his daughter to sleep. Prospero then summons his spirit, Ariel, who describes to him how the tempest has destroyed everyone on board the ship. Prospero instructs Ariel to revive them and bring them to the island.

Caliban appears, heir to the late ruler of the island, Sycorax. Prospero’s power keeps Caliban from his rightful inheritance, and he curses Prospero for mistreating him. Caliban, lusting after Miranda, is threatened by Prospero, then banished to his cave.

Ariel reports on the shipwrecked, now brought ashore and restored. Prospero orders Ariel to bring him Prince Ferdinand, son of the King of Naples. Prospero wants the King and the courtiers to suffer by thinking that Ferdinand has drowned. In exchange for this help, Ariel asks to be released from servitude. Ariel sings of the fate of Ferdinand’s father, thereby luring Ferdinand ashore. There, he finds Miranda, who wakes, thinking him a creation of Prospero’s. She wonders at the sight of another human and they fall instantly in love. Prospero is startled that his spell on Miranda has been broken and is angered by Ferdinand’s interest in his daughter. He immobilizes Ferdinand and sends Miranda away. He then calls on Ariel and prepares to further his vengeance on the rest of the court.

ACT II

Washed up on the island, the courtiers discover no trace of the storm; it is tranquil and their clothes are dry and in perfect condition. Stefano and Trinculo are confounded by the lack of damage and drunkenly relive the terror of the storm. Unseen, Prospero instructs Ariel to taunt the court. The King weeps for his lost son and Gonzalo tries to give him hope. Antonio says he saw Ferdinand swimming toward the land, but, using the voice of Sebastian, the King’s brother, Ariel insults Antonio and an argument begins. Caliban appears and is mocked by the courtiers who give him jewelry and alcohol, which he feels makes him strong. The sound of Ariel’s voice is heard, frightening the courtiers who believe it to be a ghost. They are calmed as Caliban describes the sounds and voices of the spirits of the island, which make him dream he’s in paradise. Asked who his master is, Caliban is silenced by Prospero. Gonzalo presses the group to search through the jungle for the prince.

Stefano and Trinculo doubt that Ferdinand will be found alive. Caliban tells them that his master is responsible for the disaster and asks for their help to regain his land. In exchange, Caliban falsely offers Trinculo and Stefano both Miranda’s hand in marriage and kingship of the island.

Ferdinand faces a future of imprisonment on the island, but he is comforted by the thought of Miranda. he expresses her feelings for him and Ferdinand replies in kind. This breaks Prospero’s spell and Ferdinand is released. As they leave, Prospero realizes he has lost Miranda to a stronger power than his own: love.

ACT III

Stefano and Trinculo are nearing Prospero, and Caliban contemplates his approaching freedom. Meanwhile, Ariel has led the shipwrecked on a twisted journey across the island. He asks to be released, but Prospero won’t yet let him go.

The King and courtiers enter, so weak they can hardly walk. They believe they will all die of hunger and that Ferdinand is dead. The King decides to disinherit his brother, Sebastian, and nominates Gonzalo as his heir.

Lulled by Ariel’s music, everyone falls asleep except Antonio and Sebastian. They plot to murder both the King and Gonzalo in order to seize power. Ariel wakes everyone, and Sebastian and Antonio claim to have heard strangers about. Ariel causes a strange feast to appear, which Gonzalo sees as a sign of beneficence from heaven. Gonzalo dwells on the thought of reigning over a land such as this. The food vanishes and Ariel appears as a harpy, leveling crimes against the courtiers who now face a wasting, slow extinction. Afraid, they all flee to another part of the island.

Prospero realizes that through his magic he has brought hell to the island. Miranda takes Ferdinand to Prospero and tells him that they are in love. Prospero summons Ariel to bless them. Prospero’s revenge being done, Ferdinand discovers that his father is still alive. Caliban enters and demands Miranda for himself. Miranda rejects Caliban, and Prospero immobilizes him. Ariel describes how the King and Antonio are demented with fear and horror. If he were human, Ariel would pity them. Moved by the spirit’s feelings, Prospero resolves to be merciful and vows to release Ariel within the hour.

The King and courtiers appear, and Prospero reveals himself to them. Antonio, who thought he had killed Prospero, is astonished, and the King asks to be forgiven. Prospero reveals Ferdinand and Miranda to the King, who can barely believe his son is alive. Ferdinand introduces Miranda as his wife. The courtiers are surprised to find both their prince living and their ship repaired, and the King announces the match between Naples and Milan. Prospero offers forgiveness to Antonio, who rejects it. Prospero resolves to relinquish his magic powers. As he breaks his staff, he begs Ariel to stay with him, but Ariel flies away to freedom. Caliban is left alone on the island.

Reprinted courtesy of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

Source: Metropolitan Opera